3 Deeply Profound Stories For Spiritual Living

January 5, 2024

Despite the awesome powers of technology, many of us still do not live very well. We may need to listen to one another's stories again.” — Dr. Rachel Remen

Dear PEERS subscribers,

Stories, not facts, are what holds a culture together. Sometimes, we need a meaningful and powerful story more than food in order to live. As we enter this new year, we thought we'd call in the wisdom of Dr. Rachel Naomi Remen, and her collection of profoundly touching, true stories from her time as a physician, professor, therapist, and long-term survivor of chronic illness.

Although her expertise has its roots in medicine and healthcare, the wisdom she shares with the world is for anyone who seeks to experience life in more direct and spiritual ways—opening up to mystery, awe, love, suffering, forgiveness, miracles, loss, and healing through human storytelling. Her creation of The Healer’s Art curriculum for medical students to explore these topics is now taught in more than half of American Medical schools and medical schools in 7 countries abroad. Living well, she suggests, is not about eradicating our wounds and weaknesses but understanding how they complete our identity and equip us to help others:

I think that we all feel that we’re not enough to make a difference; that we need to be more, somehow, either wealthier or more educated or different than the people we are. People ask: how can I make a difference when I’m so wounded and feel so not-enough? I tell them that it’s our very wounds that enable us to make a difference. We are the right people, just as we are. And to just wonder about that a little, what if we were exactly what’s needed? What then? How would I live if I was exactly what’s needed for whatever I am stepping into?

One of the core pioneers of integrative medicine and relationship-centered care, Dr. Remen has spent decades counseling hundreds of end-of-life people and those dealing with cancer. Her countless discoveries in this work have led her to see life as a powerful mystery, abundant with qualities and capacities that we cannot measure with our minds.

When I was an intern, first-year doctor ... we had a man come into the hospital to die. And people used to come into the hospital to die — there wasn’t a hospice movement then. And this man came in riddled with cancer. He had an osteosarcoma, and his bones looked like Swiss cheese; all these lesions were cancer, and there were big snowballs of cancer in his lungs.

And in the two weeks or so that he was with us in the hospital, all of these lesions disappeared, and they never came back. Now, were we in awe? Certainly not. We were frustrated. Obviously, someone had misdiagnosed him. So we sent the slides out to pathologists all over the country, and the pathologists sent back the slides, saying, Classic osteogenic sarcoma. So then we had a grand rounds. And the slides were shown, the X-rays were shown, the man himself was shown — and the conclusion of this large group of doctors was that the chemotherapy, which had been stopped 11 months before, had suddenly worked. Now, the embarrassing part of this story is that I believed this for the next 15 years. I never questioned this conclusion. I think too great a scientific objectivity can make you blind.

I think that that was one of the purest encounters with mystery that I have ever had in my life. It makes me wonder about who we are, what’s possible for us, how this world really operates. I have no answers, but I have a lot of questions, and those questions have helped me to live, better than any answers I might find.

— Rachel Remen, excerpt from a podcast interview with On Being

Below are three beautiful (and true) stories from her book, Kitchen Table Wisdom. We hope you enjoy and find deeper meaning in your own life through these stories.

With faith in a transforming world,

Amber Yang for PEERS and WantToKnow.info

Remembering

The Holy Shadow

The Meeting Place

Remembering

What we do to survive is often different from what we may need to do in order to live. My work as a cancer therapist often means helping people to recognize this difference, to get off the treadmill of survival, and to refocus their lives. Of the many people who have confronted this issue, one of the most dramatic was an Asian woman of remarkable beauty and style. Through our work together I realized that some things which can never be fixed can still heal.

She was about to begin a year of chemotherapy for ovarian cancer, but this is not what she talked about in our first meeting. She began our work together by telling me she was a "bad" person, hard, uncaring, selfish, and unloving. She delivered this self-indictment with enormous poise and certainty. I watched the light play across her perfect skin and the polish of her long black hair and thought privately that I did not believe her. The people I had known who were truly selfish were rarely aware of it—they simply put themselves first without doubt or hesitation.

In a voice filled with shame, Ana began to tell me that she had no heart, and that her phenomenal success in business was a direct result of this ruthlessness. Most important, she felt that it was not possible for her to become well, as she had earned her cancer through her behavior. She questioned why she had come seeking help. There was a silence in which we took each other's measure. "Why not start from the beginning?" I said.

It took her more than eight months to tell her story. She had not been born here. She had come to this country at ten, as an orphan. She had been adopted by a good family, a family that knew little about her past. With their support she had built a life for herself.

In a voice I could barely hear, she began to speak of her experiences as a child in Vietnam during the war. She began with the death of her parents. She had been four years old the morning the Cong had come, small enough to hide in the wooden box that held the rice in the kitchen. The soldiers had not looked there after they had killed the others. When at last they had gone and she ventured from hiding she had seen that her family had been beheaded. That was the beginning. I was horrified. She continued on. It had been a time of brutality, a world without mercy. She was alone. She had starved. She had been brutalized. Hesitantly at first, and then with growing openness, she told story after story. She had become one of a pack of homeless children. She had stolen, she had betrayed, she had hated, she had helped kill. She had seen things beyond human endurance, done things beyond imagination. Like a spore, she had become what was needed to survive.

As the weeks went by, there was little I could say. Over and over she would tell me that she was a bad person, "a person of darkness." I was filled with horror and pity, wishing to ease her anguish, to offer comfort.

Over and over a wall of silence and despair threatened to close us off from each other. Over and over I would beat it back, insisting that she tell me the worst. She would weep and say, "I do not know if I can," and hoping that I would be able to hear it, I would tell her that she must. And she would begin another story. I often found myself not knowing how to respond, unable to do anything but stand with her here, one foot in this peaceful calm office on the water, the other in a world beyond imagination. I had never been orphaned, never been hunted, never missed a meal except by choice, never violently attacked another person. But I could recognize the whisper of my darkness in hers and I stood in that place in myself to listen to her, to try to understand. I wanted to jump in, I wanted to soothe, I wanted to make sense, yet none of this was possible. Once, in despair myself, I remember thinking, "I am her first witness."

Over and over she would cry out, "I have such darkness in me." At such times it seemed to me that the cancer was actually helping her make sense of her life; offering the relief of a feared but long-awaited punishment.

At the close of one of her stories, I was overwhelmed by the fact that she had actually managed to live with such memories. I told her this and added, "I am in awe." We sat looking at each other. "It helps me that you say that. I feel less alone." I nodded and we sat in silence. I was in awe of this woman and her ability to survive. In all the years of working with people with cancer, I had never met anyone like her. I ached for her. Like an animal in a trap that gnaws off its own leg, she had survived but only at a terrible cost.

Gradually she began to shorten the time frame of her stories, to talk of more recent events: her ruthless business practices, how she used others, always serving her own self-interest.

She began to talk about her contempt, her anger, her unkindness, her distrust of people, and her competitiveness. It seemed to me that she was completely alone. "Nothing has really changed," I thought. Her whole life was still organized around her survival.

Once, at the close of a particularly painful session, I found myself reviewing my own day, noticing how much of the time I was focused on surviving and not on living. I wondered if I too had become caught in survival. How much had I put off living today in order to do or say what was expedient? To get what I thought I needed. Could survival become a habit? Was it possible to live so defensively that you never got to live at all?

"You have survived, Ana," I blurted out. "Surely you can stop now." She looked at me, puzzled. But I had nothing further to say. One day, she walked in and said, "I have no more stories to tell."

"Is it a relief?" I asked her. To my surprise she answered, "No, it feels empty."

"Tell me." She looked away. "I am afraid I will not know how to survive now." Then she laughed. "But could never forget,” she said.

A few weeks after this she brought in a dream, one of the first she could remember. In the dream, she had been looking in a mirror, seeing herself reflected there to the waist. It seemed to her that she could see through her clothes, through her shin, through to the very depths of her being. She saw that she was filled with darkness and felt a familiar shame, as intense as that she had felt on the first day she had come to my office. Yet the could not look away. Then it seemed to her as if she were moving, as if she had passed through into the mirror, into her own image, and was moving deeper and deeper into her darkness. She went forward blindly for a long time. Then, just as she was certain that there was no end, no bottom, that surely this would go on and on, she seemed to see a tiny spot far ahead. As she moved closer to it, she was able to recognize what it was. It was a rose. A single, perfect rosebud on a long stem.

For the first time in eight months she began to cry softly, without pain. "It's very beautiful," she told me. "I can see it very clearly, the stem with its leaves and its thorns. It is just beginning to open. And its color is indescribable: the softest, most tender, most exquisite shade of pink."

I asked her what this dream meant to her and she began to sob. "It's mine," she said. "It is still there. All this time it is still there. It has waited for me to come back for it."

The rose is one of the oldest archetypical symbols for the heart, It appears in both the Christian and the Hindu traditions and in many fairy tales. It presented itself now to Ana even though she had never read these fairy tales or heard of these traditions. For most of her life, she had held her darkness close to her, had used it as her protection, had even defined herself through it. Now, finally, she had been able to remember. There was a part she had hidden even from herself. A part she had kept safe. A part that had not been touched.

Even more than our experiences, our beliefs become our prisons. But we carry our healing with us even into the darkest of our inner places. A Course in Miracles says, "When I have forgiven myself and remembered who I am, I will bless everyone and everything I see." The way to freedom often lies through the open heart.

The Holy Shadow

There is a Sufi story about a man who is so good that the angels ask God to give him the gift of miracles. God wisely tells them to ask him if that is what he would wish.

So the angels visit this good man and offer him first the gift of healing by hands, then the gift of conversion of souls, and lastly the gift of virtue. He refuses them all. They insist that he choose a gift or they will choose one for him. "Very well," he replies. "I ask that I may do a great deal of good without ever knowing it." The story ends this way:

The angels were perplexed. They took counsel and resolved upon the following plan: Every time the saint's shadow fell behind him it would have the power to cure disease, soothe pain, and comfort sorrow. As he walked, behind him his shadow made arid paths green, caused withered plants to bloom, gave clear water to dried-up brooks, fresh color to pale children, and joy to unhappy men and women. The saint simply went about his daily life diffusing virtue as the stars diffuse light, without ever being aware of it. The people respecting his humility followed him silently, never speaking to him about his miracles. Soon they even forgot his name and called him "the Holy Shadow."

It is comforting to think that we may be of help in ways that we don't even realize. One of my own personal healers is probably completely unaware of the difference she made in my life. In fact, I do not know even her name and I am sure she has long forgotten mine.

At twenty-nine, much of my intestine was removed surgically and I was left with an ileostomy. A loop of bowel opens on my abdomen and an ingeniously designed plastic appliance, which I remove and replace every few days, covers it. Not an easy thing for a young woman to live with. While this surgery had given me back much of my vitality, the appliance and the profound change in my body made me feel hopelessly different, permanently shut out of the world of femininity and elegance.

At the beginning, before I could change my appliance myself, it was changed for me by nurse specialists called enterostomal therapists. These white-coated professionals would enter my hospital room, put on an apron, a mask and gloves and then remove and replace my appliance. The task completed, they would strip off all this protective clothing. Then they would carefully wash their hands. This elaborate ritual made things harder for me. I felt shamed.

One day a woman about my age came to do this task. It was late in the day and she was not dressed in a white coat, but in a silk dress, heels, and stockings. In a friendly way she asked if I was ready to have my appliance changed. When I nodded, she pulled back the covers, produced a new appliance, and in the most simple and natural way imaginable removed my old one and replaced it, without putting on gloves. I remember watching her hands. She had washed them carefully before she touched me. They were soft and gentle and beautifully cared for. She was wearing a pale pink nail polish and her rings were gold.

I doubt that she ever knew what her willingness to touch me in such a natural way meant to me. In ten minutes she not only tended my body, but healed my wounds and gave me hope. What is most professional is not always what is most healing.

In the past few years a great deal of attention has been paid to angels and many people have become more aware of the possibility that insight and guidance may be offered at surprising times and in surprising ways. Books have been written about meetings with such celestial messengers and the help and healing they have offered. What is not so commonly recognized is that it is not only angels that carry divine messages of healing and guidance; any one of us may be used in this same way. We are messengers for each other. The difference between us and the folks with the wings is that we often carry these messages without knowing. Like the Holy Shadow.

It has been my experience and the experience of many other therapists that when I am facing a difficult personal issue or a painful decision or am struggling with some recalcitrant and stubborn part of my self, a very peculiar thing will happen. Many of my clients will spontaneously bring in the same issue.

Completely unaware of the personal importance of the issue to me, they will work on some aspect of it as it pertains to them, all the while offering me, through their own work, guidance and perspective on the issue for my healing. Sometimes they work on the very issue or sometimes in the process of working on something else they will offer a single sentence or thought that cuts through my confusion and frees me.

I have many examples of this, but one stands out in my mind. It was a time when I discovered that a friend had incorporated some of my ideas and exercises into her best-selling book without acknowledging where she had learned them. I felt hurt and betrayed by this until my third client of the day sat down and pleasantly remarked, "You know, you can get a lot of good done in this world if you don't care who gets the credit." Astonished, I asked her what had made her think of this. "Oh," she said, "it was on the bumper sticker of the car that just pulled out of my parking spot."

Perhaps the world is one big healing community and we are a healers of each other. Perhaps we are all angels. And we do not know.

The Meeting Place

The places where we are genuinely met and heard have great importance to us. Being in them may remind us of our strength and our value in ways that many other places we may pass through do not.

My medical partner, who had never been ill a day in his life, died suddenly of a massive heart attack at fifty-six. He was a consummate healer and a magnificent friend and he left both his colleagues and his patients bereft. For weeks we numbly went through papers and made referrals for the many people who called in, many of them weeping. Finally, the last details were attended to and we settled down to a future without Hal.

Then the patients started coming. For almost a year afterwards, several times a week I would open the door of my office and find one of Hal's patients sitting in the common waiting room. At first I would worry that they didn't know about Hal and would have to tell them, but they all knew. They had just come to the place where they had experienced his listening, his special way of seeing and valuing them, just to sit there for a bit, perhaps to think about difficult decisions which currently faced them. Many patients came. It was terribly, terribly moving. It made me angry with Hal for tending every life so impeccably except his own.

Another colleague, who is the head of the department of family medicine at one of the East Coast's outstanding medical schools, tells a story about one of Hal's patients. The patient was a homeless woman whose possessions fit into two shopping carts. Once a month she would bring these up the steep hill to his clinic by lashing them alternately to the parking meters with a belt. First she would tie one, then wheel the other to the next meter uphill, tie it, go back for the first one, untie it, and wheel it to the meter above the second until both she and the two carts were at the clinic's front door. He saw her once a month on a Wednesday. Her speech was sometimes rambling and her clothing was filthy and eccentric. This deeply kind and respectful man was not troubled by this. With his usual grave courtesy he welcomed her into his consulting room, listened to the details of her difficult life, and did what he could to ease her burden.

After he had been seeing her for some time, he became aware that she sometimes came to the hospital on days when he was not there. The clinic nurses were puzzled by this at first, as she seemed to know in some mysterious way that it was not her day to see the doctor. After talking with her, they determined that she simply wanted to go to his consulting room. Once there she would stand on the threshold and slowly and deliberately place her right foot inside the empty room and then withdraw it again and again. After a while she would be satisfied and go away again.

The places in which we are seen and heard are holy places. They remind us of our value as human beings. They give us the strength to go on. Eventually they may even help us to transform our pain into wisdom.

Don't miss our treasure trove of inspiring resources

Kindly support this work of love: Donate here

www.momentoflove.org - Every person in the world has a heart

www.personalgrowthcourses.net - Dynamic online courses powerfully expand your horizons

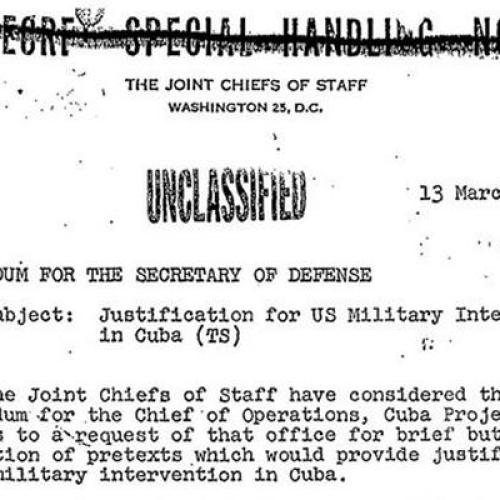

www.WantToKnow.info - Reliable, verifiable information on major cover-ups

www.weboflove.org - Strengthening the Web of Love that interconnects us all

Subscribe to the PEERS email list of inspiration and education (one email per week). Or subscribe to the list of news and research on deep politics (one email every few days).