Key Excerpts of Day After Roswell

Written by Lieutenant Colonel Philip J. Corso

Perhaps one of the most intriguing testimonies of those allegedly involved in top secret UFO government programs was the story of Lieutenant Colonel Philip J. Corso, former head of the Foreign Technology Desk in the US Army and a member of President Eisenhower‘s National Security Council from 1953–1957.

A year before his death, he came forward to share his astounding knowledge and involvement in covert government operations regarding UFO phenomena in his book Day After Roswell. In the book, he describes how he came into contact with Roswell material, and the shocking encounters he had of alien bodies. He also discusses how he helped spearhead the Army’s reverse-engineering project on recovered material from the infamous 1947 Roswell crash, which accelerated the development of sophisticated technologies commonly used today.

Below are key excerpts from his book that we found particularly useful in understanding the UFO phenomena, and the history of covert government programs regarding UFOs that are just beginning to come to light.

For context, explore the 1947 Roswell Crash Cover-Up in our comprehensive UFO Information Center.

- Introduction

- Discovering the Bodies at Fort Riley

- Artifacts from Roswell

- MJ-12 and Beyond: How Secret UFO Government Programs Formed

- Examining the Alien Bodies

- Investigating the Recovered Craft

- Surveilling Extraterrestrial Activity and Secret Moon Programs

- Transistors

- Lasers

- Fiber Optics

- Bulletproof Vests

Introduction

My name is Philip J. Corso, and for two incredible years back in the 1960s while I was a lieutenant colonel in the army heading up the Foreign Technology desk in Army Research and Development at the Pentagon, I led a double life. In my routine everyday job as a researcher and evaluator of weapons systems for the army.

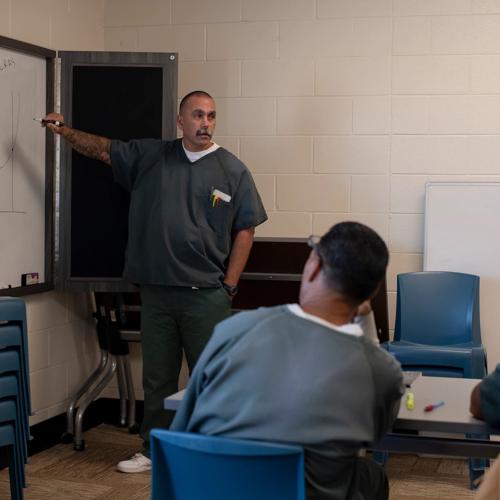

Part of my job responsibility in Army R&D, however, was as an intelligence officer and adviser to General Trudeau who, himself, had headed up Army Intelligence before coming to R&D. This was a job I was trained for and held during World War II and Korea. At the Pentagon I was working in some of the most secret areas of military intelligence, reviewing heavily classified information on behalf of General Trudeau. I had been on General Mac-Arthur's staff in Korea and knew that as late as 1961— even as late, maybe, as today—as Americans back then were sitting down to watch Dr. Kildare or Gunsmoke, captured American soldiers from World War II and Korea were still living in gulag conditions in prison camps in the Soviet Union and Korea. Some of them were undergoing what amounted to sheer psychological torture. They were the men who never returned.

As an intelligence officer I also knew the terrible secret that some of our government's most revered institutions had been penetrated by the KGB and that key aspects of American foreign policy were being dictated from inside the Kremlin. I testified to this first at a Senate subcommittee hearing chaired by Senator Everett Dirksen of Illinois in April 1962, and a month later delivered the same information to Attorney General Robert Kennedy.

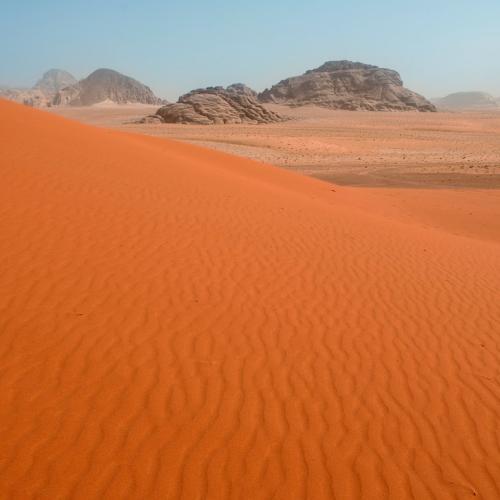

But hidden beneath everything I did, at the center of a double life I led that no one knew about, and buried deep inside my job at the Pentagon was a single file cabinet that I had inherited because of my intelligence background. That file held the army's deepest and most closely guarded secret: the Roswell files, the cache of debris and information an army retrieval team from the 509th Army Air Field pulled out of the wreckage of a flying disk that had crashed outside the town of Roswell in the New Mexico desert in the early-morning darkness during the first week of July 1947. The Roswell file was the legacy of what happened in the hours and days after the crash when the official government cover-up was put into place. As the military tried to figure out what it was that had crashed, where it had come from, and what its inhabitants' intentions were, a covert group was assembled under the leadership of the director of intelligence, Adm. Roscoe Hillenkoetter, to investigate the nature of the flying disks and collect all information about encounters with these phenomena while, at the same time, publicly and officially discounting the existence of all flying saucers. This operation has been going on, in one form or another, for fifty years amidst complete secrecy.

I wasn't in Roswell in 1947, nor had I heard any details about the crash at that time because it was kept so tightly under wraps, even within the military. You can easily understand why, though, if you remember, as I do, the Mercury Theater "War of the Worlds" radio broadcast in 1938 when the entire country panicked at the story of how invaders from Mars landed in Grovers Mill, New Jersey, and began attacking the local populace.

The fictionalized eyewitness reports of violence and the inability of our military forces to stop the creatures were graphic. They killed everyone who crossed their path, narrator Orson Welles said into his microphone, as these creatures in their war machines started their march toward New York. The level of terror that Halloween night of the broadcast was so intense and the military so incapable of protecting the local residents that the police were overwhelmed by the phone calls. It was as if the whole country had gone crazy and authority itself had started to unravel.

Now, in Roswell in 1947, the landing of a flying saucer was no fantasy. It was real, the military wasn't able to prevent it, and this time the authorities didn't want a repeat of "War of the Worlds." So you can see the mentality at work behind the desperate need to keep the story quiet. And this is not to mention the military fears at first that the craft might have been an experimental Soviet weapon because it bore a resemblance to some of the German-designed aircraft that had made their appearances near the end of the war, especially the crescent-shaped Horton flying wing. What if the Soviets had developed their own version of this craft?

The stories about the Roswell crash vary from one another in the details. Because I wasn't there, I've had to rely on reports of others, even within the military itself.

In 1961, regardless of the differences in the Roswell story from the many different sources who had described it, the top-secret file of Roswell information came into my possession when I took over the Foreign Technology desk at R&D. My boss, General Trudeau, asked me to use the army's ongoing weapons development and research program as a way to filter the Roswell technology into the mainstream of industrial development through the military defense contracting program.

Today, items such as lasers, integrated circuitry, fiber-optics networks, accelerated particle-beam devices, and even the Kevlar material in bulletproof vests are all commonplace. Yet the seeds for the development of all of them were found in the crash of the alien craft at Roswell and turned up in my files fourteen years later.

But that's not even the whole story.

In those confusing hours after the discovery of the crashed Roswell alien craft, the army determined that in the absence of any other information it had to be an extraterrestrial. Worse, the fact that this craft and other flying saucers had been surveilling our defensive installations and even seemed to evidence a technology we'd seen evidenced by the Nazis caused the military to assume these flying saucers had hostile intentions and might have even interfered in human events during the war.

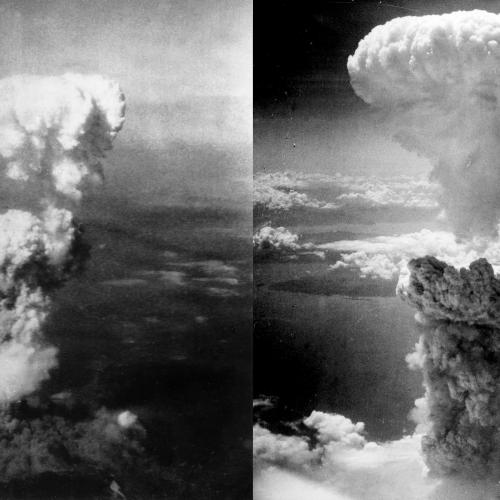

That meant that we were facing a far superior power with weapons capable of obliterating us. At the same time we were locked in a Cold War with the Soviets and the mainland Chinese and were faced with the penetration of our own intelligence agencies by the KGB.

The military found itself fighting a two-front war, a war against the Communists who were seeking to undermine our institutions while threatening our allies and, as unbelievable as it sounds, a war against extraterrestrials, who posed an even greater threat than the Communist forces. It took us until the 1980s, but in the end we were able to deploy enough of the Strategic Defense Initiative, "Star Wars," to achieve the capability of knocking down enemy satellites, killing the electronic guidance systems of incoming enemy warheads, and disabling enemy spacecraft, if we had to, to pose a threat. It was alien technology that we used: lasers, accelerated particle-beam weapons, and aircraft equipped with "Stealth" features.

I just did my job, going to work at the Pentagon day in and day out until we put enough of this alien technology into development that it began to move forward under its own weight through industry and back into the army. The full import of what we did at Army R&D and what General Trudeau did to grow R&D from a disorganized unit under the shadow of the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), when he first took command, to the army department that helped create the military guided missile, the antimissile missile, and the guided-missile-launched accelerated particle-beam-firing satellite killer, didn't really hit me until years later when I understood just how we were able to make history.

I always thought of myself as just a little man from a little American town in western Pennsylvania, and I didn't assess the weight of our accomplishments at Army R&D, especially how we harvested the technology coming out of the Roswell crash, until thirty-five years after I left the army when I sat down to write my memoirs for an entirely different book. That was when I reviewed my old journals, remembered some of the memos I'd written to General Trudeau, and understood that the story of what happened in the days after the Roswell crash was perhaps the most significant story of the past fifty years.

Throughout the 1950s, I witnessed the government become more and more secretive about UFOs even though privately I thought that they would get better information if they were more open about it. But I was also a military officer and understood the necessity of keeping information confidential until you understood what it was. Besides, the Soviets were making great strides in the race to get into space and we didn't know if they were getting cooperation from the EBEs.

In 1961, the air force began two secret projects that, in effect, had been in operation since 1947 but had not been committed to policy. "Moon Dust" had to do with the establishment of recovery teams to retrieve and recover crashed or grounded "foreign" space vehicles. But for all intents and purposes, as far as the public was concerned the air force was looking for Soviet satellites that had fallen out of the sky and landed on Earth. But in reality the air force was establishing a recovery of UFOs program just like the army had pulled the crashed UFO out of the New Mexico desert fourteen years earlier. Then in Project "Blue Fly," the air force authorized the immediate delivery of foreign crashed space vehicles and any other item of technical intelligence interest to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, for evaluation. It was a repeat of General Twining's retrieval of the Roswell space vehicle from the 509th to Wright Field in 1947.

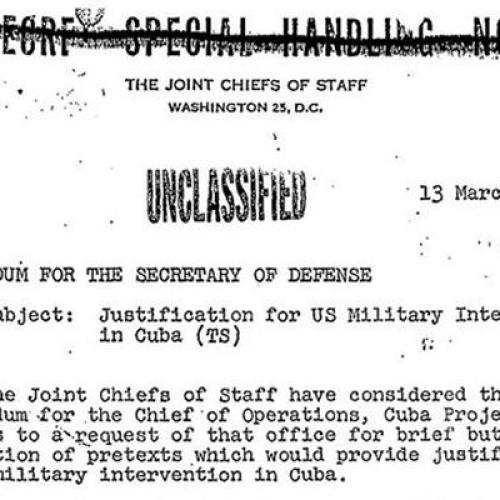

In 1962, one of the assistants to the secretary of defense, Arthur Sylvester, told the press at a briefing that if the government deemed it necessary for reasons of national security, it would not even furnish information about UFOs to Congress, let alone the American public.

So, believe it or not, this is the story of what happened in the days after Roswell and how a small group of military intelligence officers changed the course of human history.

Back to top.Discovering the Bodies at Fort Riley

Whatever was going on, I didn’t want to play any games. The post duty sheet for that night read that the veterinary building was off-limits to everyone. Not even the sentries were allowed inside because whatever had been loaded in had been classified as “No Access.”

“Brownie, you know you’re not supposed to be in there,” I said. “Get out here and tell me what’s going on.” [Brownie was M.Sgt. Bill Brown]

He stepped out from inside the door, and even through the shadow I could see that his face was a dead pale, just as if he’d seen a ghost.

“You won’t believe this,” he said. “I don’t believe it and I just saw it.”

“What are you talking about?” I asked.

“The guys who off-loaded those deuce-and-a-halfs,” he said. “They told us they brought these boxes up from Fort Bliss from some accident out in New Mexico? … Well, they told us it was all top secret but they looked inside anyway. Everybody down there did when they were loading the trucks. MPs were walking around with sidearms and even the officers were standing guard,” Brown said.

“But the guys who loaded the trucks said they looked inside the boxes and didn’t believe what they saw. You got security clearance, Major. You can come in here.”

In fact, I was the post duty officer and could go anywhere I wanted during the watch. So I walked inside the old veterinary building, the medical dispensary for the cavalry horses before the First World War, and saw where the cargo from the convoy had been stacked up. There was no one in the building except for Bill Brown and myself.

“What is all this stuff?” I asked.

“That’s just it, Major, nobody knows,” he said. “The drivers told us it came from a plane crash out in the desert somewhere around the 509th. But when they looked inside, it was nothing like anything they’d seen before. Nothing from this planet.”

There were about thirty-odd wooden crates nailed shut and stacked together against the far wall of the building. The light switches were the push type and I didn’t know which switch tripped which circuit, so I used my flashlight and stumbled around until my eyes got used to the darkness and shadows. I didn’t want to start pulling apart the nails, so I set the flashlight off to one side where it could throw light on the stack and then searched for a box that could open easily. Then I found an oblong box off to one side with a wide seam under the top that looked like it had been already opened. It looked like either the strangest weapons crate you’d ever see or the smallest shipping crate for a coffin. Maybe this was the box that Brownie had seen. I brought the flashlight over and set it up high on the wall so it would throw as broad a beam as possible. Then I set to work on the crate.

The top was already loose. I was right—this one had just been opened. I jimmied the top back and forth, continuing to loosen the nails that had been pried up with a nail claw, until I felt them come out of the wood. Then I worked along the sides of the five-or-so-foot box until the top was loose all the way around. Not knowing which end of the box was the front, I picked up the top and slid it off to the edge. Then I lowered the flashlight, looked inside, and my stomach rolled right up into my throat and I almost became sick right then and there.

Whatever they’d crated this way, it was a coffin, but not like any coffin I’d seen before. The contents, enclosed in a thick glass container, were submerged in a thick light blue liquid, almost as heavy as a gelling solution of diesel fuel. But the object was floating, actually suspended, and not sitting on the bottom with a fluid over top, and it was soft and shiny as the underbelly of a fish. At first I thought it was a dead child they were shipping somewhere. But this was no child. It was a four-foot human-shaped figure with arms, bizarre-looking four-fingered hands—I didn’t see a thumb—thin legs and feet, and an oversized incandescent lightbulb-shaped head that looked like it was floating over a balloon gondola for a chin. I know I must have cringed at first, but then I had the urge to pull off the top of the liquid container and touch the pale gray skin. But I couldn’t tell whether it was skin because it also looked like a very thin one-piece head-to-toe fabric covering the creature’s flesh.

Its eyeballs must have been rolled way back in its head because I couldn’t see any pupils or iris or anything that resembled a human eye. But the eye sockets themselves were oversized and almond shaped and pointed down to its tiny nose, which didn’t really protrude from the skull. It was more like the tiny nose of a baby that never grew as the child grew, and it was mostly nostril. The creature’s skull was overgrown to the point where all of its facial features—such as they were—were arranged absolutely frontally, occupying only a small circle on the lower part of the head. The protruding ears of a human were nonexistent, its cheeks had no definition, and there were no eyebrows or any indications of facial hair. The creature had only a tiny flat slit for a mouth and it was completely closed, resembling more of a crease or indentation between the nose and the bottom of the chinless skull than a fully functioning orifice. I would find out years later how it communicated, but at that moment in Kansas, I could only stand there in shock over the clearly nonhuman face suspended in front of me in a semiliquid preservative.

I could see no damage to the creature’s body and no indication that it had been involved in any accident. There was no blood, its limbs seemed intact, and I could find no lacerations on the skin or through the gray fabric. I looked through the crate encasing the container of liquid for any paperwork or shipping invoice or anything that would describe the nature or origin of this thing. What I found was an intriguing Army Intelligence document describing the creature as an inhabitant of a craft that had crash-landed in Roswell, New Mexico, earlier that week and a routing manifest for this creature to the log-in officer at the Air Materiel Command at Wright Field and from him to the Walter Reed Army Hospital morgue’s pathology section where, I supposed, the creature would be autopsied and stored. It was not a document I was meant to see, for sure, so I tucked it back in the envelope against the inside wall of the crate.

I allowed myself more time to look at the creature than I should have, I suppose, because that night I missed the time checks on the rest of my rounds and believed I’d have to come up with a pretty good explanation for the lateness of my other stops to verify the sentry assignments. But what I was looking at was worth any trouble I’d get into the next day. This thing was truly fascinating and at the same time utterly horrible. It challenged every conception I had.

I slid the top of the crate back over the creature, knocked the nails loosely into their original holes with the butt end of my flashlight, and put the tarp back in position. Then I left the building and hoped I could close the door forever on what I’d seen. Just forget it, I told myself. You weren’t supposed to see it and maybe you can live your whole life without ever having to think about it. Maybe. Once outside the building I rejoined Brownie at his post.

“You know you never saw this,” I said. “And you tell no one.”

Back to top.Artifacts from Roswell

It was 1961, four years after I left the White House and put on my uniform again to stand guard across the electronic no-man’s-land of radar sweeps and photo sensors just a few kilometers west of the Iron Curtain. My new boss was General Arthur Trudeau, one of the last fighting generals from the Korean War.

I was a lieutenant colonel when I came to the Pentagon in 1961, and all I brought with me were my bowling trophy from Fort Riley and a nameplate for my desk cut out of the fin of a Nike missile from Germany.

General Trudeau gave me his very grim smile and said, as he walked me toward the locked dark olive military file cabinet on the wall of his private office, “I need you to cover my back, Colonel. I need you to watch because what I’m going to do, I can’t cover it myself.”

Whatever Trudeau was planning, I knew he’d tell me in his own time. And he’d tell me only what he thought I needed to know when I needed it. For the immediate present, I was to be his special assistant in R&D, one of the most sensitive divisions in the whole Pentagon bureaucracy because that was where the most classified plans of the scientists and weapons designers were translated into the reality of defense contracts. R&D was the interface between the gleam in someone’s eye and a piece of hardware prototype rolling out of a factory to show its potential for the army brass. Only it was my job to keep it a secret while it was developed.

The general had put me in an office on the second floor of the outer ring directly under him. That way, as I would soon find out, whenever he needed me in a hurry I could get upstairs and through the back door before anybody even knew where I was. “This has some special files, war material you’ve never seen before, that I want to put under your Foreign Technology responsibilities,” he continued.

My specific assignment was to the Research & Development Division’s Foreign Technology desk, what I thought would be a pretty dry post because it mainly required me to keep up on the kinds of weapons and research our allies were doing.

“I’ll get to those files right away if you like, General,” I said. “And write up some preliminary reports on what I think about it.”

“It’s going to take you a little longer than that, Phil,” Trudeau said. Now he was almost laughing, something he didn’t do very much in those days. In fact, the only time I remember him laughing that way was after he heard that his name had been put up to command the U.S. forces in Vietnam.

“Is there something else about this I should know, General?” I asked, trying not to show any hesitation in my voice. Business as usual, nothing out of the ordinary, nothing anybody can throw my way that I can’t handle.

“Actually, Phil, the material in this cabinet is a little different from the run-of-the-mill foreign stuff we’ve seen up to now,” he said. “I don’t know if you’ve ever seen the intelligence on what we’ve got here when you were over at the White House, but before you write up any summaries maybe you should do a little research on the Roswell file.”

I remembered a hot July night fourteen years before at Fort Riley when I was the young intelligence officer after having just been shipped back from Rome. I remembered being hustled into a storage hangar by one of the sentries, a fellow member of the Fort Riley bowling team. What he pointed to under the thick olive tarp that night was also very, very secret, and I held my breath, hoping that what was inside this cabinet wasn’t anything like what I saw that night in Kansas, July 6, 1947.

I opened the cabinet, and almost immediately my heart sank. I knew, from looking at the shoebox of tangled wires and the strange cloth, from the visorlike headpiece and the little wafers that looked like Ritz crackers only with broken edges and colored a dark gray, and from an assortment of other items that I couldn’t even relate to the shapes and sizes of things I was familiar with, that my life was headed for a big change.

After I went to the White House and saw all the National Security Council memos describing the “incident” and talking about the “package” and the “goods,” I knew that the strange figure I’d seen floating in liquid in a casket within a casket at Fort Riley wasn’t just a bad dream I could forget about.

I heard footsteps outside my door and caught my breath. There were always sounds in the Pentagon at night because the building was never empty. Somewhere, in some office, in parts of the building most people don’t even know about, some group is planning for a war we hope we will never fight.

General Trudeau peeked his head around the door. “Look inside?” he asked.

“What’d you do to me, General?” I said. “I thought we were friends.”

“That’s why I gave you this, Phil,” he said, but he wasn’t laughing, wasn’t even smiling. “You know how valuable this property is? You know what any of the other agencies would do to get this into their hands?”

“They’d probably kill me,” I said.

“They probably want to kill you anyway, but this makes them even more rabid. The air force wants it because they think it belongs to them. The navy wants it because they want anything the air force wants. The CIA wants it so they can give it to the Russians.”

“I need a plan from you,” he said. “Not simply what this property is, but what we can do with it. Something that keeps it out of play until we know what we have and what use we can make of it.”

“Look, who’s our biggest problem?” I asked, but it was a pro forma question because I already knew the answer.

“The same people who lost Korea for us and who you had to fight over at the White House,” he said. “You know exactly who I mean. We got to keep whatever’s valuable here from falling into the wrong hands because as sure as we’re standing in this Pentagon, it’ll find its way right to the Kremlin.”

There were people floating around Washington right at that very moment who, even out of the most well-meaning intentions they could muster, would have shipped this Roswell file over to Russia while patting President Kennedy on the back and congratulating him for contributing to world peace. Just as there were people who would have cut Trudeau’s and my throat and left us right on the rug to bleed to death while they packed that file away. Either way, Trudeau didn’t have to quote me chapter and verse to explain that he was handing me one of the most important assignments I would ever receive from him. He was giving me the keys to a whole new kingdom, but neither he nor I knew what in the world we could do with this stuff, short of keeping it out of the hands of the Russians. At the very least, that was a start.

Career after career of anyone in government who even hinted at the big dark secret of Roswell was pulverized by whoever was behind this operation. And, although I knew far more than I had even admitted to myself, I would never be the one to shoot off my mouth. But now this file, what I would eventually call the “nut file” to General Trudeau, had come into my possession, and as the ensuing weeks turned into a month, I gradually figured out where some of the puzzle pieces fit.

First there were the tiny, clear, single-filament, flexible glasslike wires twisted together through a kind of gray harness as if they were cables going into a junction. They were narrow filaments, thinner than copper wire. As I held the harness of strands up to the light from my desk, I could see an eerie glow coming through them as if they were conducting the faint light and breaking it up into different colors. When the personnel at the retrieval site in the desert outside of Roswell pulled this piece out of the wreckage of the delta-shaped object, they thought it was some sort of wiring device—a harness is what they said—or maybe some of them thought it was a junction box or electrical relay. But whatever they thought it was, they believed there was nothing like it on this planet. As I turned the object over in my hand, I figured, from the way the individual filaments flexed back and forth but didn’t break and the way they were able to conduct a light beam along their length, they were a wire of some sort. But for what purpose I didn’t have a clue.

Then there were the thin two-inch-around matte gray oyster cracker–shaped wafers of a material that looked like plastic but had tiny road maps of wires barely raised/etched along the surface. They were the size of a twenty-five-cent piece, but the etchings on the surface reminded me of squashed insects with their hundred legs spread out at right angles from a flat body. Some were more rounded or elliptical. It was a circuit—anyone could figure that out by 1961, especially when you put it under a magnifying glass—but from the way these wafers were stacked on each other, this was a circuitry unlike any other I’d ever seen. I couldn’t figure out how to plug it in and what kind of current it carried, but it was clearly a wire circuitry of a sort that came from a larger board of wafers on board the flying craft. My hand shook ever so slightly as I held these pieces, not because they themselves were scary but because I was awed, just for a few seconds, about the momentous nature of this find.

I was most interested in the file descriptions accompanying a two-piece set of dark elliptical eyepieces as thin as skin. The Walter Reed pathologists said they adhered to the lenses of the extraterrestrial creatures’ eyes and seemed to reflect existing light, even in what looked like complete darkness, so as to illuminate and intensify images in the darkness to allow their wearer to pick out shapes. The reports had said that the pathologists at Walter Reed hospital who autopsied one of these creatures tried to peer through them in the darkness to watch the one or two army sentries and medical orderlies walking down a corridor adjacent to the pathology lab. These figures were illuminated in a greenish orange, depending upon how they moved, but the pathologists could see only their outer shape. And when they got close to each other, their shapes blended into a single form. But they could also see the outlines of furniture and the wall and objects on desktops. Maybe, I thought as I read this report, soldiers could wear a visor that intensified images through the reflection and amplification of available light and navigate in the darkness of a battlefield with as much confidence as if they were walking their sentry posts in broad daylight. But these eyepieces didn’t turn night into day, they only highlighted the exterior shapes of things.

There was a dull, grayish-silvery foil-like swatch of cloth among these artifacts that you could not fold, bend, tear, or wad up but that bounded right back into its original shape without any creases. It was a metallic fiber with physical characteristics that would later be called “supertenacity,” but when I tried to cut it with scissors, the arms just slid right off without making even a nick in the fibers. If you tried to stretch it, it bounced back, but I noticed that all the threads seemed to be going in one direction. When I tried to stretch it widthwise instead of lengthwise, it looked like the fibers had reoriented themselves to the direction I was pulling in. This couldn’t be cloth, but it obviously wasn’t metal. It was a combination, to my unscientific eye, of a cloth woven with metal strands that had the drape and malleability of a fabric and the strength and resistance of a metal. I was on top of some of the most secret weapons projects at the Pentagon, and we had nothing like this, even under the wish-list category.

There was a written description and a sketch of another device, too, like a short, stubby flashlight almost with a self-contained power source that was nothing at all like a battery. The scientists at Wright Field who examined it said they couldn’t see the beam of light shoot out of it, but when they pointed the pencil-like flashlight at a wall, they could see a tiny circle of red light, but there was no actual beam from the end of what seemed like a lens to the wall as there would have been if you were playing a flashlight off on a distant object. When they passed an object in front of the source of the light, it interrupted it, but the beam was so intense the object began smoking. They played with this device a lot before they realized that it was an alien cutting device like a blowtorch. One time they floated some smoke across the light and suddenly the whole beam took shape. What had been invisible suddenly had a round, microthin, tunnel-like shape to it.

Then there was the strangest device of all, a headband, almost, with electrical-signal pickup devices on either side. I could figure out no use for this thing whatsoever unless whoever used it did so as a fancy hair band. It seemed to be a one-size-fits-all headpiece that did nothing, at least not for humans. Maybe it picked up brain waves like an electroencephalogram and projected a chart. But no private experiment conducted on it seemed to do anything at all. The scientists didn’t even determine how to plug it in or what its source of power was because it came with no batteries or diagrams.

Back to top.MJ-12 and Beyond: How Secret UFO Government Programs Formed

Like the navy, the air force had different advocates for different goals, and so did the army. And when there are competing agendas and strategies articulated by some of the best and brightest people ever to graduate from universities, war colleges, and the ranks of officers, you have hard-nosed people playing high-stakes games against one another for the big prizes: the lion’s share of the military budget. And, at the very center of it all, the place where the dollars get spent, are the weapons-development people who work for their respective branches of the military.

And within those first few weeks I saw and learned a lot about how the politics of the Roswell discovery had matured over the fourteen years since the crash and since the intense discussions at the White House after Eisenhower became president. Each of the different branches of the military had been protecting its own cache of Roswell-related files and had been actively seeking to gather as much new Roswell material as possible. Certainly all the services had their own reports from examiners at Walter Reed and Bethesda concerning the nature of the alien physiology. Mine were in my nut file along with the drawings. It was pretty clear, also, from the way the navy and air force were formulating their respective plans for advanced military-technology hardware, that many of the same pieces of technology in my files were probably shared by the other services. But nobody was bragging because everybody wanted to know what the other guy had. But since, officially, Roswell had never happened in the first place, there was no technology to develop.

On the other hand, the curiosity among weapons and intelligence people within the services was rabid. Nobody wanted to come in second place in the silent, unacknowledged alien-technology-development race going on at the Pentagon as each service quietly pursued its version of a secret Roswell weapon. If you were in the know about what was retrieved from Roswell, you kept your ears open for snippets of information about what was being developed by another branch of the military, what was going before the budget committees for funding, or what defense contractors were developing a specific technology for the services. If you weren’t in the Roswell loop, but were too curious for your own good, you could be spun around by the swirling rumor mill that the Roswell race had kicked up among competing weapons-development people in the services and wind up chasing nothing more than dust devils that vanished down the halls as soon as you turned the corner on them.

As if the eyes of the other military services weren’t enough, we also had to contend with the analysts from the Central Intelligence Agency. Under the guise of coordination and cooperation, the CIA was amalgamating as much power as it could. Information is power, and the more the CIA tried to learn about the army weapons-development program, the more nervous it made all of us at the center of R&D.

“How does the CIA know what we have?” [I said to General Trudeau.]

“They’re guessing, I suppose,” he said. “And figuring it out by the process of elimination. Look, everybody suspects what the air force has.”

Trudeau was right. In the rumor bank from which everybody in the Pentagon made deposits and withdrawals, the air force was sitting on the Holy Grail—a spaceship itself and maybe even a live extraterrestrial. Nobody knew for sure. We knew that after it became a separate branch of the military in 1948, the air force kept some of the Roswell artifacts at Wright Field outside of Dayton, Ohio, because that’s where “the cargo” was shipped, stopping off in Fort Riley along the way. But the air force was primarily interested in how things fly, so whatever R&D they worked on was focused on how their planes could evade radar and outfly the Soviets no matter where we got the technology from.

“And,” he continued, “I’m sure the agency fellows would love to get into the Naval Intelligence files on Roswell if they’ve not done so already.” With its advanced submarine technology and missile-launching nuclear subs, the navy was struggling with its own problem in figuring out what to do about UUOs or USOs—Unidentified Submerged Objects, as they came to be called. It was a worry in naval circles, particularly as war planners advanced strategies for protracted submarine warfare in the event of a first strike. Whatever was flying circles around our jets since the 1950s, evading radar at our top-secret missile bases like Red Canyon, which I saw with my own eyes, could plunge right into the ocean, navigate down there just as easy as you please, and surface halfway around the world without so much as leaving an underwater signature we could pick up. Were these USOs building bases at the bottom of oceanic basins beyond the dive capacity of our best submarines, even the Los Angeles–class jobbies that were only on the drawing boards? That’s what the chief of Naval Operations had to find out, so the navy was occupied with fighting its own war with extraterrestrial craft in the air and under the sea.

That left the army.

However we were going to camouflage our development of the Roswell technology, it had to be within the existing way we did business so no one would recognize any difference. We operated on a normal defense development projects budget of well into the billions in 1960, most of it allocated to the analysis of new weapons systems. Just within our own bureau we had contracts with the nation’s biggest defense companies with whom we maintained almost daily communication.

Luckily enough for me, the whole Roswell story was still unknown outside the highest military circles in 1961. Retired major Jesse Marcel, the intelligence officer at the 509th who had been at the crash site in July 1947 and who had given the initial reports of a spacecraft, would not yet tell his story in public for at least another ten years. Everyone else connected to the incident was either dead or sworn to silence.

The air force, which moved quickly to take over management of the Roswell affair and ongoing UFO contacts and sightings, still kept everything they learned highly classified under the Air Force Intelligence Command and waged a push-and-pull war with the CIA for information about sightings and ongoing contacts with anything extraterrestrial. These really weren’t my concerns yet, but they would be.

My research was not concerned with the crash at Roswell itself ... but on the day after Roswell, the day Bill Blanchard from the 509th crated up the alien debris and shipped it to Fort Bliss, where Gen. Roger Ramey’s staff determined its final disposition and the official government history of the event began to unfold.

In the early hours after the cargo arrived in Texas, there was so much confusion about what was found and what wasn’t found that army officers, who were in charge of the entire retrieval operation, quickly scraped together both a cover story and a plan to silence all the military and civilian witnesses to the recovery.

The cover story was easy. General Ramey ordered Maj. Jesse Marcel to recant his “flying saucer” story and pose for a news photo with debris from a weather balloon, which he described as the wreckage the retrieval team recovered from outside Roswell. Marcel followed orders and the flying saucer officially became a weather balloon.

The silencing worked so well that for the next thirty years the story seemed to have been swallowed up by the quiet emptiness of desert where all things are worn down to a fine grade of sameness. But belying the quiet that settled over Roswell, a thousand miles away, part of the U.S. military went on wartime alert as bits and pieces of the craft reached their destinations. One of those destinations, Lt. Gen. Nathan Twining’s desk at Wright Field, was the focal point from which the Roswell artifacts would reach the Foreign Technology desk at the Pentagon. Among the first of the army’s top commands notified of the events unfolding in Roswell in early July would have had to have been Lieutenant General Twining’s Air Materiel Command at Wright Field, where the Roswell debris was shipped. Nathan Twining has become important to UFO researchers because of his association with a number of highly secret meetings at the Eisenhower White House having to do with the national security issues posed by the discovery of UFOs and his relationship to National Security Special Assistant Robert Cutler, who was the liaison between the NSC and President Eisenhower when I was on the NSC staff in the 1950s. The silver-haired General Twining was the point man for initial research and dissemination of Roswell-related materials.

General Twining had seen the material for himself, and even before he returned to Wright Field, he’d conferred with the rocket scientists who were part of his brain trust at Alamogordo. Now, during the remainder of the summer months, he quietly compiled a report that he would deliver to President Truman and an ad hoc group of military, government, and civilian officials, who would ultimately become the chief policy makers for what would become an ongoing contact with extraterrestrials over the ensuing fifty years.

The first of these reports was transmitted from General Twining to the commanding general of Army Air Forces in Washington, dated September 23, 1947. Written to the attention of Brig. Gen. George Schulgen, Twining’s memo addressed, in the most general of terms, the official Air Materiel Command’s intelligence regarding “flying discs.”

Flying saucers or UFOs are not illusions, Twining says, referring to the sighting of strange objects in the sky as “something real and not visionary or fictitious.” Even though he cites the possibility that some of the sightings are only meteors or other natural occurrences, he says that the reports are based upon real sightings of actual objects “approximating the shape of a disc, of such appreciable size as to be as large as man-made aircraft.” Considering that this report was never intended for public scrutiny, especially in 1947, Twining marveled at the aircrafts’ operating characteristics and went on record, drawing major conclusions about the material he had and the reports he’d heard or read. His characterization of the aircrafts’ behavior revealed, even weeks after the physical encounter, that those officers in the military who were now running the yet-to-be-code-named extraterrestrial contact project already considered these objects and those entities who controlled them a military threat. He described the aircraft as it had been reported in the sightings: a “light reflective or metallic surface,” “absence of a trail except in those few instances when the object was operating under high performance conditions,” “circular or elliptical in shape, flat on bottom and domed on top,” flights in formation consisting of from “three to nine objects,” and no sound except for those instances when “a substantial rumbling roar was noted.” The objects moved quickly for aircraft at that time, he noted to General Schulgen, at level flight speeds above three hundred knots.

Were the United States to build such an aircraft, especially one with a range of over seven thousand miles, the cost, commitment, administrative and development overhead, and drain on existing high-technology projects required that the entire project should be independent or outside of the normal weapons-development bureaucracy. In other words, as I interpreted the memo, Twining was suggesting to the commander of the Army Air Force that were the air force, which would become a separate branch of the military by the following year, to attempt to exploit the technology that had quite literally dropped into its lap, it had to do so separately and independently from any normal weapons-development program. The descriptions of the supersecret projects at Nellis Air Force Base or Area 51 in the Nevada desert seem to fit the profile of the kind of recommendation that General Twining was making, especially the employment of the “skunk works” group at Lockheed in the development of the Stealth fighter and B2 bomber.

Three days after the memo, on September 26, 1947, General Twining gave his report on the Roswell crash and its implications for the United States to President Truman and a short list of officials he convened to begin the management of this top-secret combination of inquiry, police development, and “ops.” This working group, which included Adm. Roscoe H. Hillenkoetter, Dr. Vannevar Bush, Secretary James Forrestal, Gen. Hoyt Vandenberg, Dr. Detlev Bronk, Dr. Jerome Hunsaker, Sidney W. Souers, Gordon Gray, Dr. Donald Menzel, Gen. Robert M. Montague, Dr. Lloyd V. Berkner, and Gen. Nathan Twining himself, became the nucleus for an ongoing fifty-year operation that some people have called “Majestic-12.”

As more information on sightings and encounters came rolling in through every imaginable channel, from police officers taking reports from frightened civilians to airline pilots tracking strange objects in the sky, the group realized that they needed policies on how to handle what was turning into a mass-media phenomenon. They needed a mechanism for processing the thousands of flying saucer reports that could be anything from a real crash or close encounter to a couple of bohunks tossing a pie tin into the air and snapping its picture with their Aunt Harriet’s Kodak Brownie. The group also had to assess the threat from the Soviet Union and Iron Curtain countries, assuming of course that flying saucers weren’t restricted to North America, and gather intelligence on what kinds of information our allies had on flying saucers as well. And it still had to process the Roswell technology and figure out how it could be used. So from the original group there developed a whole tree structure of loosely confederated committees and subgroups, sometimes complete organizations like the air force Project Blue Book, all kept separate by administrative firewalls so that there would be no information leakage, but all controlled from the top.

With the initial and ongoing stories safely covered up, the plans for the long-term reverse-engineering work on the Roswell technology could begin. But who would do it? Where would the material reside? And how could the camouflage of what the military was doing be maintained amidst the push for new weapons, competition with the Soviets, and the flying saucer mania that was sweeping the country in the late 1940s? General Twining had a plan for that, too.

Just a little over a year after the initial group meetings at the White House, Air Force Intelligence, now that the air force had become a separate service, issued a December 1948 report—100-203-79—called “Analysis of Flying Object Incidents in the U.S.” in which UFOs are never referred to as extraterrestrial objects but as elements of “foreign technology,” which is actually the subject of the report. The report, innocuous to most people because it doesn’t say that flying saucers came from outer space, is actually one of the first indications showing how the camouflage plan was supposed to work over the ensuing years.

The writers of the report had located within the existing military administrative structure the precise place where all research and development into the flying disk phenomenon could be pursued not only under a veil of secrecy but in the very place where no one could be expected to look: the Foreign Technology desk. Here, the materials could be deposited for safekeeping within the military while army and air force brass decided what our existing industrial and research technology allowed them to do. There could be fiascoes as weapons failed, secret experiments without fear of exposure, and, most importantly, an ongoing discussion of how the United States could develop this treasure trove of engineering information, all within the very structure where it was supposed to take place. Just don’t call it extraterrestrial; call it “foreign technology” and throw it into the hopper with the rest of the mundane stuff the foreign technology officers were supposed to do.

And that’s how, twelve years later, the Roswell technology turned up in an old combination-locked military file cabinet carted into my new Pentagon office by two of the biggest enlisted men I’d ever seen.

General Twining had made it clear in his preliminary analysis that they were investigating the whole phenomenon of flying disks, including Roswell and any other encounter that happened to take place. [These entities] had a technology vastly superior to ours, which we had to study and exploit. If we were forced to fight a war in outer space, we would have to understand the nature of the enemy better, especially if it came to preparing the American people for an enemy they had to face. So investigate first, he suggested, but prepare for the day when the whole undertaking would have to be disclosed.

This, Truman could understand. He had trusted Twining to manage this potential crisis from the moment Forrestal had alerted him that the crash had taken place. And Twining had done a brilliant job. He kept the lid on the story and brought back everything that he could under one roof. He understood as Twining described to him the strangeness of the spacecraft that seemed to have no engines, no fuel, nor any apparent methods of propulsion, yet outflew our fastest fighters; the odd childlike creatures who were inside and how one of them was killed by a gunshot; the way you could see daylight through the inside of the craft even though the sun had not yet risen; the swatches of metallic fabric that they couldn’t burn or melt; thin beams of light that you couldn’t see until they hit an object and then burned right through it, and on and on; more questions than answers. It would take years to find these answers, Twining had said, and it was beyond the immediate capacity of our military to do anything about it. This will take a lot of manpower, the general said, and most of the work will have to be done in secret.

General Twining showed photographs of these alien beings and autopsy reports that suggested they were too human; they had to be related to our species in some way. They were obviously intelligent and able to communicate, witnesses at the scene had reported, by some sort of thought projection unlike any mental telepathy you’d see at a carnival show. We didn’t know whether they came from a planet like Mars in our own solar system or from some galaxy we could barely see with our strongest telescopes. But they possessed a military technology whose edges we could understand and exploit, even if only for self-defense against the Soviets.

By the middle of September it was obvious to every member of President Truman’s working group, which included the following:

Central Intelligence Director Adm. Roscoe Hillenkoetter

Secretary of Defense James Forrestal

Lt. Gen. Nathan Twining of the AAF and then USAF Air Materiel Command

Professor Donald Menzel, Harvard astronomer and Naval Intelligence cryptography expert

Vannevar Bush, Joint Research and Development Board Chairman

Detlev Bronk, Chairman of the National Research Council and biologist who would ultimately be named to the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics

Gen. Robert Montague, who was General Twining’s classmate at West Point, Commandant of Fort Bliss with operational control over the command at White Sands

Gordon Gray, President Truman’s Secretary of the Army and chairman of the CIA’s Psychological Strategy Board

Sidney Souers, Director of the National Security Council

Gen. Hoyt Vandenberg, Central Intelligence Group Director prior to Roscoe Hillenkoetter and then USAF Chief of Staff in 1948

Jerome Hunsaker, aircraft engineer and Director of the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics

Lloyd Berkner, member of the Joint Research and Development Board

It would have to be, General Twining suggested, at the same time both the greatest cover-up and greatest public relations program ever undertaken.

The group agreed that these were the requirements of the endeavor they would undertake. They would form nothing less than a government within the government, sustaining itself from presidential administration to presidential administration regardless of whatever political party took power, and ruthlessly guarding their secrets while evaluating every new bit of information on flying saucers they received. But at the same time, they would allow disclosure of some of the most far-fetched information, whether true or not, because it would help create a climate of public attitude that would be able to accept the existence of extraterrestrial life without a general sense of panic.

“It will be,” General Twining said, “a case where the cover-up is the disclosure and the disclosure is the cover-up. Deny everything, but let the public sentiment take its course. Let skepticism do our work for us until the truth becomes common acceptance.”

Meanwhile, the group agreed to establish an information-gathering project, ultimately named Blue Book and managed explicitly by the air force, which would serve public relations purposes by allowing individuals to file reports on flying disk sightings. While the Blue Book field officers attributed commonplace explanations to the reported sightings, the entire project was a mechanism to acquire photographic records of flying saucer activity for evaluation and research. The most intriguing sightings that had the highest probability of being truly unidentified objects would be bumped upstairs to the working group for dissemination to the authorized agencies carrying on the research. For my purposes, when I entered the Pentagon, the general category of all flying disk phenomena research and evaluation was referred to simply as “foreign technology.”

Project “Blue Book” was created to make the general public happy that they had a mechanism for reporting what they saw. Projects “Grudge” and “Sign” were of a higher security to allow the military to process sightings and encounter reports that couldn’t easily be explained away as balloons, geese, or the planet Venus. Blue Fly and Twinkle had other purposes, as did scores of other camouflage projects like Horizon, HARP, Rainbow, and even the Space Defense Initiative, all of which had something to do with alien technology. But no one ever knew it. And when reporters were actually given truthful descriptions of alien encounters, they either fell on the floor laughing or sold the story to the tabloids, who’d print a drawing of a large-headed, almond-eyed, six-fingered alien. Again, everybody laughed. But that’s what these things really look like because I saw the one they trucked up to Wright Field.

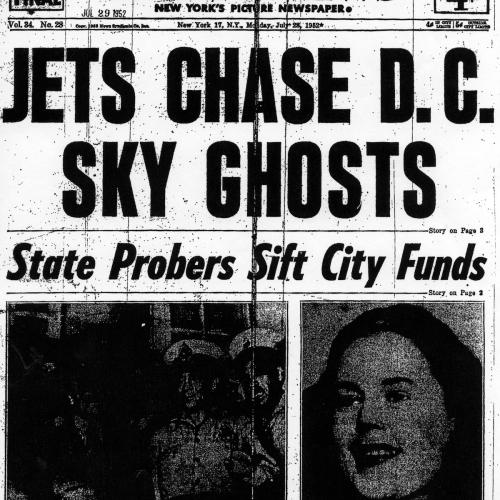

Meanwhile, as each new project was created and administered, another bread crumb for anyone pursuing the secrets to find, we were gradually releasing bits and pieces of information to those we knew would make something out of it. Flying saucers did truly buzz over Washington, D.C., in 1952, and there are plenty of photographs and radar reports to substantiate it. But we denied it while encouraging science fiction writers to make movies like The Man from Planet X to blow off some of the pressure concerning the truth about flying disks. This was called camouflage through limited disclosure, and it worked. If people could enjoy it as entertainment, get duly frightened, and follow trails to nowhere that the working group had planted, then they’d be less likely to stumble over what we were really doing. And what were we really doing?

What had started out as a single-purpose camouflage operation was breaking up into smaller units. Command-and-control functions started to weaken and, just like a submarine that breaks up on the bottom of the ocean, debris in the form of information bubbled to the surface. Army CIC, once a powerful force to keep the Roswell story itself suppressed, had weakened under the combined encroachments of the CIA and the FBI. It was during this period that my old friend J. Edgar Hoover, never happy at being kept out of any loop, jumped into the circle and very quietly began investigating the Roswell incident. This shook things up, and very soon afterward, other government agencies—the ones with official reporting responsibilities—began poking around as well.

For all intents and purposes, the original scheme to perpetrate a camouflage was defunct by the late 1950s. Its functions were now being managed by series of individual groups within the military and civilian intelligence agencies, all still sharing limited information with each other, each pursuing its own individual research and investigation, and each—astonishingly—still acting as if some super intelligence group was still in command. But, like the Wizard of Oz, there was no super intelligence group. Its functions had been absorbed by the groups beneath it. But nobody bothered to tell anyone because a super group was never supposed to exist officially in the first place. That which did not exist officially could not go out of existence officially. Hence, right through the next forty years, the remnants of what once was a super group went through the motions, but the real activities were carried out by individual agencies that believed on blind faith that they were being managed by higher-ups.

So we began to devise a strategy.

“Hypothetically, Phil,” Trudeau laid the question out. “What’s the best way to exploit what we have without anybody knowing we’re doing anything special?”

“We start the same way this desk has always started: with reports,” I said. “I’ll write up reports on the alien technology just like it’s an intelligence report on any piece of foreign technology. What I see, what I think the potential may be, where we might be able to develop, what company we should take it to, and what kind of contract we should draw up.”

“Where will you start?” the general asked.

“I’ll line up everything in the nut file,” I began. “Everything from what’s obvious to what I can’t make heads or tails out of. And I’ll go to scientists with clearance who we can trust, Oberth and von Braun, for advice.”

“I see what you mean,” Trudeau acknowledged. “Sure. We’ll line up our defense contractors, too. See which ones have ongoing development contracts that allow us to feed your development projects right into them.”

“Exactly. That way the existing defense contract becomes the cover for what we’re developing,” I said. “Nothing is ever out of the ordinary because we’re never starting up anything that hasn’t already been started up in a previous contract.”

“It’s just like a big mix and match,” Trudeau described it.

“Only what we’re doing, General, is mixing technology we’re developing in with technology not of this earth,” I said. “And we’ll let the companies we’re contracting with apply for the patents themselves.”

“Of course,” Trudeau realized. “If they own the patent we will have completely reverse-engineered the technology.”

“Yes, sir, that’s right. Nobody will ever know. We won’t even tell the companies we’re working with where this technology comes from. As far as the world will know the history of the patent is the history of the invention.”

“It’s the perfect cover, Phil,” the general said. “Where will you start?”

Back to top.Examining the Alien Bodies

“The photographs in my file,” I began my report that night over the autopsy reports, which I attached, show a being of about 4 feet tall. The body seemed decomposed and the photos themselves aren’t of much use except to the curious. It’s the medical reports that are of interest. The organs, bones, and skin composition are different from ours. The being’s heart and lungs are bigger than a human’s. The bones are thinner but seem stronger as if the atoms are aligned differently for a greater tensile strength. The skin also shows a different atomic alignment in a way that appears the skin is supposed to protect the vital organs from cosmic ray or wave action or gravitational forces that we don’t yet understand. The overall medical report suggests that the medical examiners are more surprised at the similarities between the being found in the spacecraft (note: NSC reports refer to this creature as an Extraterrestrial Biological Entity [EBE]) and human beings than they are at the differences, especially the brain which is bigger in the EBE but not at all unlike ours.

If we consider similar biological factors that affect human beings, like long distance runners whose hearts and lungs are larger than average, hill and mountain dwellers whose lung capacity is greater than those who live closer to sea level, and even natural athletes whose long striated muscle alignment is different from those who are not athletes, can we not assume that the EBEs who have fallen into our possession represent the end process of genetic engineering designed to adapt them to long space voyages within an electromagnetic wave environment at speeds which create the physical conditions described by Einstein's General Theory of Relativity? (Note for the record: Dr. Hermann Oberth suggests we consider the Roswell craft from the New Mexico desert not a spacecraft but a time machine. His technical report on propulsion will follow.)

The medical report and supporting photographs in front of me suggested that the creature was remarkably well adapted for long-distance space travel.

For example, biological time, the Walter Reed medical examiners hypothesized, must have passed very slowly for the entity because it possessed a very slow metabolism, evidenced, they said, by the enormous capacities of the huge heart and lungs. The physiology of this thing indicated that this was not a creature whose body had to work hard to sustain it. A larger heart, my ME's report read, meant that it took fewer beats than an average human heart to drive the thin, milky, almost lymphatic-like fluid through a limited, more primitive-looking, and apparently reduced-capacity circulatory system. As a result, the biological clock beat more slowly than a human's and probably allowed the creature to travel great distances in a shorter biological time than humans.

It seemed to them that our atmosphere was quite toxic to the creature's organs. Given the time that passed between the crash of the vehicle and the creature's arrival at Walter Reed, it decomposed all of the organs far more rapidly than it would have decomposed human organs. This fact particularly impressed me because I had seen one of these things, if not the very one described in the report, suspended in a gel-like substance at Fort Riley. So whatever exposure it must have had was very minimal by human standards because the medical personnel at the 509th's Walker Field got it into a liquid preservation state very quickly. Nevertheless, the Walter Reed pathologists were unable to determine with any certainty the structure of the creature's heart except to guess that because it functioned as a passive blood-storage facility as well as a pumping muscle that it didn't work the same way as did a four-chambered human heart. They said the alien heart seemed to have had internal diaphragm-like muscles that worked less hard than human heart muscle did because the creatures were meant to survive within a reduced gravity field as we understand gravity.

As camels store water, so did this creature store whatever atmosphere it breathed in the large capacity of its lungs. The lungs functioned in ways similar to a camel's humps or to our scuba tanks and released atmosphere very slowly into the creature's system. Because of the large heart and the storage function we believed it had, we also surmised that it took far less breathable atmosphere to sustain the creature, thereby reducing the need for carrying large volumes of atmosphere along on the voyage. Perhaps the aircraft had a means of recirculating its atmosphere, recycling spent or waste air back into the craft. Moreover, because the creatures were only four or so feet tall, the large lungs occupied a far greater percentage of the chest cavity than human lungs did, further impressing the pathologists who examined the creatures' remains.

If we believed the heart and lungs seemed bioengineered for long-distance travel so, too, was the creature's skeletal tissue. Although it was in a state of advanced decomposition, the creature's bones looked to the army medical examiners to be fibrous, actually thinner than comparable human bones such as the ribs, sternum, clavicle, and pelvis. Pathologists speculated that the bones were more flexible than human bones and had a resiliency that might be related to the function of shock absorbers. More brittle human bones might more easily shatter under the stresses these alien entities must have been routinely subjected to. However, with a flexible skeletal frame, these entities appeared well suited for potential shocks and physical traumas of extreme forces and could withstand the fractures that would cripple human space travelers in a similar environment.

There was much speculation from the different medical analysts about what these beings were composed of and what could have sustained them. First of all, doctors were more tantalized by the similarities the creatures shared with us than they were concerned about the differences. Rather than hideous-looking insects or the reptilian man-eaters that attacked Earth in War of the Worlds, these beings looked like little versions of us, only different. It was eerie.

Of specific interest was the fluid that served as blood but also seemed to regulate bodily functions in much the same way glandular secretions do for the human body. In these biological en-tities, the blood system and lymphatic systems seem to have been combined. And if an exchange of nutrients and waste occurred within their systems, that exchange could have only taken place through the creature's skin or the outer protective covering they wore because there were no digestive or waste systems.

The medical report revealed that the creatures were enclosed within a one-piece protective covering like a jumpsuit or outer skin in which the atoms were aligned so as to provide a great tensile strength and flexibility. One examiner wrote that it reminded him of a spider's web, which appears very fragile but is, in fact, very strong.

The unique qualities of a spiderweb result from the alignment of fibers that provide great tenacity because they're able to stretch under great pressure, yet display a resiliency that allows them to snap back into shape even after the shock of an impact. Similarly, the creature's spacesuit or outer skin appeared to be stretched around it as if it were literally spun over the creature and seized up around it, providing a perfect skin-tight protective fit. The doctors had never seen anything like it before.

The lengthwise alignment of the fibers in the suit also prompted the medical analysts to suggest that the suit might have been capable of protecting the wearer against the low-energy cosmic rays that would routinely bombard any craft during a space journey. The interior organs of the creature seemed so fragile and oversized that the Walter Reed medical analysts imagined that without the suit the entity would have been vulnerable to the cumulative physical trauma from a constant energy particle bombardment. Space travel without protection from subatomic particle bombardment might subject the traveler to the same kind of effects he'd experience if he were cooked in a microwave oven. The particle bombardment inside the craft, if heavy enough to constitute a shower, would so excite and accelerate the creature's atomic structure that the resulting heat energy would literally cook the entity up.

The Walter Reed doctors were also fascinated by the nature of the creature's inner skin. It resembled, although their preliminary reports didn't go into any chemical analysis, a thin layer of fatty tissue unlike any they'd ever seen before. And it was completely permeable, as if it were constantly exchanging chemicals back and forth with the combination blood/lymphatic system. Was this the way the creatures nourished themselves during their journeys and was this how waste was processed? The very small mouths and the lack of a human digestive system troubled the doctors at first because they didn't know how these things were sustained. But their hypothesis that they processed chemicals released from their skin and maybe even recirculated waste chemicals would have explained the lack of any food-preparation or waste-processing facilities on the craft. I speculated, however, that they didn't require food or facilities for waste disposal because they weren't actual life-forms, only a kind of robot or android.

Another explanation, of course, suggested by the engineers at Wright Field, is that there would have been no need for food-preparation facilities had this craft been only a small scout ship that didn't venture far from a larger craft. The creatures' low metabolism meant that they could survive extended periods away from the main craft by subsisting on some form of military prepackaged foods until they returned to base. Neither the Wright Field engineers nor the Walter Reed medical examiners had an explanation for the lack of waste disposal on board the craft, nor could they explain how the creatures' waste was processed. Maybe I was speculating too far about robots or androids when I was writing my report for General Trudeau, but I kept thinking, also, that the skin analysis that I was reading sounded more akin to the skin of a houseplant than the skin of a human being. That, too, could have been another explanation for the lack of food or waste facilities.

Much credence also was given to the firsthand descriptions of on-scene witnesses who said they received impressions from the dying creature that it was suffering and in great pain. No one heard the creature make any sounds, so any impressions, Army Intelligence personnel assumed, would have to have been created through some type of empathic projection or outright mental telepathy. But witnesses said they heard no "words" in their mind, only the resonance of a shared or projected impression much simpler than a sentence but far more complex because they were able to share with the creature a sense not only of suffering but of profound sadness, as if it were in mourning for the others who perished on board the craft. These witness reports intrigued me more than any other information we took from the crash site.

Where the possibility of some evidence about the workings of the alien brains did exist was in what I referred to in my reports as the "headbands." Among the artifacts we retrieved were devices that looked something like headbands but had neither adornment nor decoration of any kind. Embedded by some very advanced kind of vulcanizing process into a form of flexible plastic were what we now know to have been electrical conductors or sensors, similar to the conductors on an electroencephalograph or polygraph. This band was fitted around the part of the alien cranium just above the ears where the skull began to expand to accommodate the large brain. At the time, the field reports from the crash and the subsequent analysis at Wright Field indicated that the engineers at the Air Materiel Command thought these might be communication devices, like the throat mikes our pilots wore during World War II. But, as I would find out when I evaluated the device and sent it into the market for reverse-engineering, this was a throat mike only in a way that a primitive stylus can be considered the forerunner of the color laser-imaging printer.

Suffice it to say that in the few hours the material was at Walker Field in Roswell, more than one officer at the 509th gingerly slipped this thing over his head and tried to figure out what it did. At first it did nothing. There were no buttons, no switches, no wires, nothing that could even be considered to have been a control panel. So no one knew how to turn it on or off. Moreover, the band was not really adjustable, though it had enough elasticity to have been one-size-fits-all for the creatures whose skulls were large enough to accommodate them.

However, the reports I read stated, the few officers whose heads were just large enough to have made contact with the full array of conductors got the shocks of their lives.

In their descriptions of the headband, these officers reported everything from a low tingling sensation inside their heads to a searing headache and a brief array of either dancing or exploding colors on the insides of their eyelids as they rotated the device around their head and brought the sensors into contact with different parts of their skull.

These eyewitness reports suggested to me that the sensors stimulated different parts of the brain while at the same time exchanged information with the brain. Again, using the analogy of an EEG, these devices were a very sophisticated mechanism for translating the electrical impulses inside the creatures' brains into specific commands. Perhaps these headband devices comprised the pilot interface of the ship's navigational and propulsion system combined with a long-range communications device. At first I didn't know, but it was only when we began development of the long brain-wave research project toward the end of my tenure at the Pentagon that I realized just what we had and how it might be developed. It took a long time to harvest this technology, but fifty years after Roswell, versions of these devices eventually became a component of the navigational control system for some of the army's most sophisticated helicopters and will soon be on the American consumer electronics market as user-input devices for personal computer games.

The first Army Air Force analysts and engineers both at the 509th and at Wright Field were also bedeviled by the lack of any traditional controls and propulsion system in the crashed vehicle. Looking at their reports and the artifacts from the perspective of 1961, however, I imagined that the keys to understanding what made the craft go and directed its flight lay not only within the craft itself but in the relationship between the pilots and the craft. If we hypothesized a brain-wave guidance system that was as specific to the pilots' electronic signature as it was to the spacecraft's, then we were looking at an entirely revolutionary concept of guided flight in which the pilot was the system. Imagine transportation devices in which the key to the ignition is a digitized code derived from your electroencephalographic signature and is read automatically upon your donning some sort of sensorized headband. That's the way I believed the spacecraft was navigated, by direct interaction between the electronic waves generated within the minds of the pilots and the craft's directional controls. The electronic brain signals were interpreted and transmitted by the headband devices, which served as interfaces.

Back to top.Investigating the Recovered Craft

When the air force became a separate branch of the service, the remaining bodies, stored at Wright, along with the spacecraft, were sent to Norton Air Force Base in California, where the air force began experiments to replicate the technology of the vehicle. This made sense. The air force cared about the flight capabilities of the craft and how to build defenses against it.

Experiments were carried out at Norton and ultimately at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada, at the famous Groom Lake site where the Stealth technology was developed. The army cared only for the weapons systems aboard the craft and how they could be reengineered for our own use. The original Roswell spacecraft remained at Norton, however, where the air force and CIA maintained a kind of alien technology museum, the final resting place of the Roswell spacecraft. But experiments in replicated alien craft continued to be carried on through the years as engineers tried to adapt the propulsion and navigation systems to our level of technology. This continues to this very day, almost in plain sight for people with security clearance who are taken to where the vehicles are kept. Over the years, the replicated vehicles have become an ongoing, inner-circle saga among top-ranking military officers and members of the government, especially the favored senators and members of the House who vote along military lines. Those who are shown the secrets are immediately bound by national secrecy legislation and cannot reveal what they saw. Thus, the official camouflage is maintained despite the large number of people who really know the truth. I admit I've never seen the craft at Norton with my own eyes, but enough reports passed across my desk during my years at Foreign Technology so that I knew what the secret was and how it was maintained.

There were no conventional technological explanations for the way the Roswell craft's propulsion system operated. There were no atomic engines, no rockets, no jets, nor any propeller-driven form of thrust. Those of us in R&D from all three branches of the service tried for years to adapt the craft's drive system to our own technology, but, through the 1960s and 1970s, fell short of getting it operational. The craft was able to displace gravity through the propagation of magnetic wave, controlled by shifting the magnetic poles around the craft so as to control, or vector, not a propulsion system but the repulsion force of like charges. Once they realized this, engineers at our country's primary defense contractors raced among themselves to figure out how the craft could retain its electric capacity and how the pilots who navigated it could live within the energy field of a wave. At issue was not only a great discovery, but the nuts-and-bolts chance to land multibillion-dollar development contracts for a whole generation of military air and undersea craft.