The

Dear PEERS subscribers,

In September, a Southern California city adopted a first-of-its-kind ordinance. The Ojai City Council made legal history by becoming the first city in the US to recognize the legal right of a nonhuman animal. The deeper meaning of the ordinance points to the recognition that a sustainable, just, and free future belongs to all life on Earth.

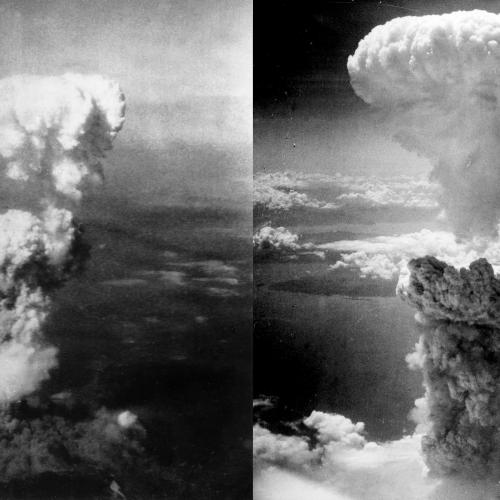

For centuries, animals have been exploited, abused, deliberately harmed and killed at the hands of humans. Animal welfare scandals have led to massive calls for compassion and corporate accountability. Earlier this year, it was discovered that the Pentagon was intentionally wounding animals through radio frequency wave testing in attempts to induce and determine the causes of “Havana Syndrome,” a mysterious ailment that was afflicting US diplomats and government officials.

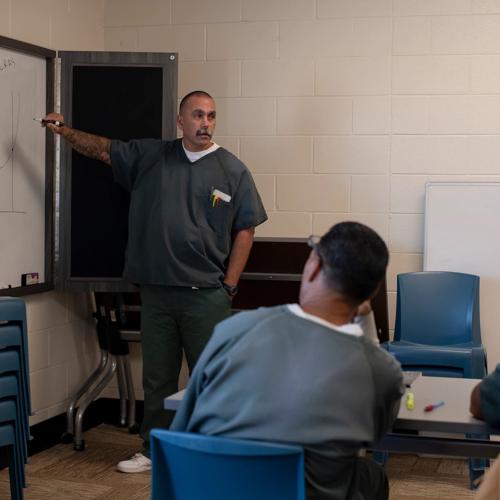

At PEERS and WantToKnow.info, we’ve summarized over 3,000 inspiring news articles since the beginning of our organization in 2003. Within this collection, we’ve summarized countless stories about the incredible skills, emotional intelligence, and sentient capacities of animals. From sniffing out cancer and deadly land mines, helping people rehabilitate in prison and learn how to trust, serving as a better pest control than pesticides, and rescuing a suicidal girl, we’ve included below some of the most remarkable stories of animals and what they’re capable of. We hope you enjoy!

With faith in a transforming world,

Amber Yang for PEERS and WantToKnow.info

Secretive White House Surveillance Program Gives Cops Access to Trillions of US Phone Records

November 20, 2023, Wired

https://www.wired.com/story/hemisphere-das-white-house-surveillance...

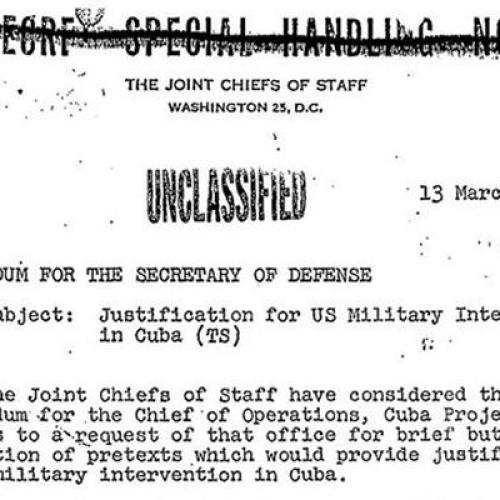

A surveillance program now known as Data Analytical Services (DAS) has for more than a decade allowed federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies to mine the details of Americans’ calls, analyzing the phone records of countless people who are not suspected of any crime, including victims. Using a technique known as chain analysis, the program targets not only those in direct phone contact with a criminal suspect but anyone with whom those individuals have been in contact as well. The DAS program, formerly known as Hemisphere, is run in coordination with the telecom giant AT&T, which captures and conducts analysis of US call records for law enforcement agencies, from local police and sheriffs’ departments to US customs offices and postal inspectors across the country, according to a White House memo reviewed by WIRED. Records show that the White House has provided more than $6 million to the program, which allows the targeting of the records of any calls that use AT&T’s infrastructure—a maze of routers and switches that crisscross the United States. Documents released under public records laws show the DAS program has been used to produce location information on criminal suspects and their known associates, a practice deemed unconstitutional without a warrant in 2018. Orders targeting a nexus of individuals are sometimes called “community of interest” subpoenas, a phrase that among privacy advocates is synonymous with dragnet surveillance.

Kindly support this work of love: Donate here

www.momentoflove.org - Every person in the world has a heart

www.personalgrowthcourses.net - Dynamic online courses powerfully expand your horizons

www.WantToKnow.info - Reliable, verifiable information on major cover-ups

www.weboflove.org - Strengthening the Web of Love that interconnects us all

Subscribe to the PEERS email list of inspiration and education (one email per week). Or subscribe to the list of news and research on deep politics (one email every few days).