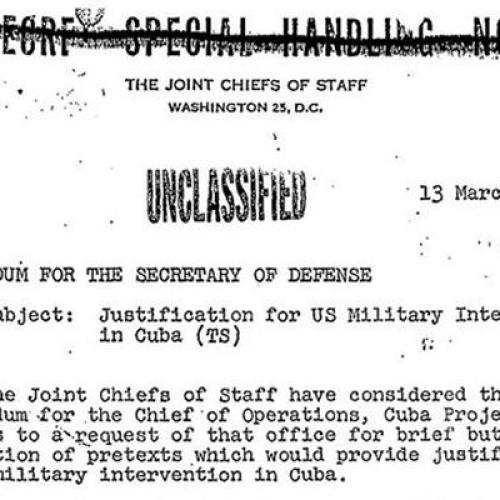

9/11 Cover-up Document

Ames Anthrax Spores Collected Over Seven Decades Destroyed

New York Times Website Requires Payment to View Article

Free Copy Given Below

This is one of the articles on the 9/11 summary for which the media website requires payment. For the New York Times website, you must both register as a member (which is free), and then pay a small fee by credit card on line in order to be able to view or download the full article. Once registered, you can view an abstract of the article for no cost. First, go to:

http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F70E1FFE3C5C0C7A8CDDA80994D9404482

If you haven't previously signed up as a user, fill in the required information. Once complete, you will see the abstract and have the option to view and download the full article with payment. We provide a copy of the article below for free. The sections referring to the Ames anthrax spores collected over seven decades being destroyed is highlighted in bold for your viewing convenience.

November 9, 2001, Friday

NATIONAL DESK

A NATION CHALLENGED: THE INQUIRY

Experts See F.B.I. Missteps Hampering Anthrax Inquiry

This article was reported and written by William J. Broad, David Johnston, Judith Miller and Paul Zielbauer. (NYT) 3123 words

The federal inquiry into the anthrax attacks has stumbled in several areas and may have missed opportunities to gather valuable evidence as criminal investigators have been unable to fully grasp the scientific complexities of the case.

Government officials, scientists and investigators said the Federal Bureau of Investigation's initial unfamiliarity with the intricacies of anthrax had contributed to a series of missteps and other possible errors.

The F.B.I. came under withering criticism this week in Congress for the lack of progress in the investigation, and bureau officials acknowledged in interviews that they had been forced to turn to outside experts for advice on how to investigate the most serious bioterrorism attack in the nation's history. But they said the inquiry was following a logical strategy.

In a plan announced yesterday by Attorney General John Ashcroft, the bureau, and other parts of the Justice Department, would be revamped to better prevent terror attacks, and the government would use new powers to tap lawyer-client conversations with defendants in terrorist cases. [Page B1.]

Several experts, including some on whom the F.B.I. has relied, said the anthrax investigation had taken some wrong turns.

Shortly after the first case of anthrax arose, the F.B.I. said it had no objection to the destruction of a collection of anthrax samples at Iowa State University, but some scientists involved in the investigation now say that collection may have contained genetic clues valuable to the inquiry.

Criminal investigators have not visited many of the companies, laboratories and academic institutions with the equipment or capability to make the kind of highly potent anthrax sent in a letter to Senator Tom Daschle, the majority leader. Where investigators have conducted interviews, they often seemed to ask general questions unlikely to elicit new evidence, several laboratory directors said.

Just this week, more than a month after the first death from inhalation anthrax, the F.B.I. issued a subpoena asking laboratories for the names of all workers and researchers who had been vaccinated against anthrax. And the F.B.I. is only now establishing electronic bulletin boards to allow members of scientific groups to interact with criminal investigators working the case.

''The bureau was caught almost as unaware and unprepared as the public was for these events,'' said Bill Tobin, a former forensic metallurgist who worked for the F.B.I. crime laboratory in Washington. ''It's just unrealistic to ask 7,000 agents to overnight become sufficiently knowledgeable about bioterrorist agents and possible means of theft of those items and how they might be disseminated lethally to an American populace.''

There is no reason to believe that any of the investigators' actions contributed to their inability to identify clear leads in the anthrax attacks that have killed four people and led to the treatment of thousands of others.

John Collingwood, the F.B.I.'s spokesman, said last night: ''We have a plan and are proceeding based in large part on what the people we are consulting with told us would be the most productive places to begin. We reached out to scientists and public health officials on the best way to proceed.''

Asked about the course of the bureau's

investigation, a senior F.B.I. official who spoke on condition of

anonymity said: ''This is a learning curve for everybody. Every single

day, if not hourly, we're all learning something about this. If you take

several weeks back, the learning curve, we were all behind it.''

Evidence Disappears

Last month, after consulting with the F.B.I., Iowa State University in Ames destroyed anthrax spores collected over more than seven decades and kept in more than 100 vials. A variant of the so-called Ames strain had been implicated in the death of a Florida man from inhalation anthrax, and the university was nervous about security.

Now, a dispute has arisen, with scientists in and out of government saying the rush to destroy the spores may have eliminated crucial evidence about the anthrax in the letters sent to Congress and the news media.

If the archive still existed, it would by no means solve the mystery. But scientists said a precise match between the anthrax that killed four people and a particular strain in the collection might have offered hints as to when that bacteria had been isolated and, perhaps, how widely it had been distributed to researchers. And that, in turn, might have given investigators important clues to the killer's identity.

Martin E. Hugh-Jones, an anthrax expert at Louisiana State University who is aiding the federal investigation, said the mystery is likely to persist. ''If those cultures were still alive,'' he said, they could have helped in ''clearing up the muddy history.''

Ronald M. Atlas, president-elect of the American Society of Microbiology, the world's largest group of germ professionals, based in Washington, said the legal implications could be large. ''Potentially,'' he said, ''it loses evidence that would have been useful'' in the criminal investigation.

The F.B.I. says it never explicitly approved the destruction of the cultures, but never objected either.

A law enforcement official said that when approached by the Ames laboratory about the destruction of its anthrax inventory, the Omaha F.B.I. office consulted with the Miami F.B.I. office, which was responsible for the initial anthrax case in Florida. He said Miami investigators, after consulting with scientists, had advised the Omaha office that the Ames strain was so widespread that it had no investigative or evidentiary value. ''Based on that there were no objections,'' to the destruction of the material by the Iowa laboratory, the official said.

Several experts said the episode underscored how the bureau traditionally has had trouble understanding the language, and the demands, of science.

''There's a chasm between what's going on in the courtroom and forensic arena,'' said Mr. Tobin, the former F.B.I. scientist, who has criticized the bureau's investigative methods. The flow of scientific data, he said, ''just doesn't seem to make it'' into criminal investigations.

And a senior federal scientist familiar with the germ investigation added: ''You're still dealing with the mentality that says anthrax is anthrax is anthrax, and doesn't realize that there are deeper signatures.''

Intertwined with the mystery of the Ames strain's history is the question of whether it was used in America's abandoned effort to develop anthrax as a weapon from 1943 to 1969, when President Richard M. Nixon renounced germ warfare.

The scientific literature is contradictory. A 1986 paper by Army researchers said the strain did not arise until 1980. But a paper in 2000 by Dr. Hugh-Jones, Paul J. Jackson of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, Paul Keim of Northern Arizona University and five other anthrax researchers asserted that the Ames strain had played a central role in the biological warfare program in the United States.

If true, that could raise the question of whether the perpetrators of the current crimes had learned of the American recipe or even found and exploited lost anthrax stockpiles.

Caree Vander Linden, spokeswoman for the Army's germ defense laboratory at Fort Detrick, Md., said officials there had not investigated whether the Ames strain was used in the old weapons program.

The Iowa State archive was destroyed on Oct. 10 and 11, after relatively brief deliberations with the F.B.I., said Julie Johnson, an official in environmental and safety at Iowa State.

It is unclear if the F.B.I. understood that Iowa State had destroyed many strains of anthrax or that the origins of the Ames strain were cloudy. Larry Holmquist, a spokesman for the F.B.I. in Omaha, which runs the bureau's Iowa operations, said the rationale for the destruction was that the strain had been ''sent out to numerous places'' around the globe in the past ''40 or 50 years.''

Tom Ridge, the White House director of homeland security, confirmed publicly that the tainted letters contained the Ames strain on Oct. 25, two weeks after the destruction.

Iowa State says it won destruction approval not only from the F.B.I. but also from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which are involved in the federal investigation.

James A. Roth, a microbiologist at the College of Veterinary Medicine who presided over the destruction, said the university's records on its anthrax strains were extremely limited and that the labeling on the vials themselves was often cryptic, leaving officials unsure exactly how many strains the university had.

Even so, ''we think they had all the strains already,'' he said of the F.B.I. and the C.D.C.

The oldest strain in the collection dated to 1928. If the Ames strain was similarly old, experts said, it is conceivable that the potent germs were distributed far more widely than conventional wisdom holds.

Since the destruction, Dr. Roth said, the

university has heard nothing from the bureau about anthrax. As for

whether the destroyed strains might have clarified the origins of Ames,

he said, ''now we'll never know.''

Questioning Scientists

The F.B.I. has been pressing its investigation in New Jersey, where the letters originated.

When two men from the F.B.I. and the New Jersey State Police arrived last month at the Waksman Institute of Microbiology at Rutgers University in New Jersey, scientists there saw it as a natural step in the anthrax investigation.

Staffed with microbiologists familiar with how the deadly bacteria grow and filled with the sophisticated laboratory equipment involved, the institute, just 38 miles from the Trenton post offices where the letters were postmarked, was a natural place for investigators to ask detailed questions.

But the two investigators, escorted by the university's head of security, asked the laboratory's director, Dr. Joachim Messing, only a few general questions about growing bacteria and never mentioned specifically what they were looking for. Finally, Dr. Messing said, he felt obligated to volunteer that his laboratory did not handle anthrax.

''I couldn't give you a clue what they were after,'' Dr. Messing said in an interview this week. ''I asked the person from the F.B.I. if he knows anything about bacteria, some very simple questions, and it was very clear that he didn't have the background to make evaluations.''

Tracking the F.B.I.'s investigation near Trenton, and beyond, shows that agents seemed to have passed over some potential opportunities for developing leads.

Though investigators are consulting some members of professional organizations like the American Society for Microbiology and the American College of Veterinary Microbiologists, the F.B.I. is only now establishing an Internet bulletin board to permit members of those groups to pass information to the bureau's leadership, a senior F.B.I. official said.

''That's in the works,'' he said.

Top bureau officials also appeared to be unaware of last month's international chemical and pharmaceutical convention, ChemShow, in New York City, which attracted hundreds of chemical and pharmaceutical equipment manufacturers, engineers and technicians.

''If they weren't crawling around that show, they should have been,'' said Richard Barbini, a chemical engineer and salesman for Arde Barinco Inc., in Norwood, N.J., a pharmaceutical equipment maker. ''There's all kinds of people there from many different countries, a lot of people who know a lot'' about what it takes to make anthrax.

The senior F.B.I. official said he was not sure if any agents had attended the show, and a bureau spokeswoman said the agency would not comment on the matter.

In New Jersey, the F.B.I. has been in regular contact with the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey in Newark, which works with infectious bacteria, but special agents have yet to call bacteria experts at the university's Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in Piscataway, said Michael A. Gallo, a professor of environmental community medicine.

F.B.I. officials say that their investigation is proceeding methodically in an uncharted area and that questions will eventually be asked in all appropriate places.

Several microbiologists suggested that agents should focus on companies that sell new and used laboratory equipment that could reduce anthrax to the micron-size particles found in the letter sent to Mr. Daschle's office last month. That equipment would include either a jet mill or a spray dryer, each of which can be used to reduce bacteria into ultrafine, inhalable powder.

Some companies that deal in that equipment said F.B.I. agents had called seeking detailed information, while others said they had been asked only general questions. Others said they had not been called at all.

A sales official at Spray Drying Systems Inc., of Randallstown, Md., a company that sells spray dryers, said the company had not heard from investigators.

But agents from the Boston F.B.I. office visited some companies, including Sturtevant Inc. in Hanover, Mass., which manufactures jet mills, said a company executive who asked that his name not be used.

''He was asking very good questions,'' the executive said of the agent.

Eventually, the executive said, he gave the agent lists of his customers and competitors. ''There's dozens and dozens and dozens of used equipment dealers out there,'' he said. ''Even the F.B.I. doesn't have enough people to track down the number of machines that are in commerce in the world.''

Though they are still compiling a complete list of places anthrax is stored in this country, federal investigators have already visited a number of laboratories, germ warehouses, universities, government agencies and even veterinarians in their search for clues in the anthrax attacks, one federal investigator involved in the inquiry said.

So far, he said, a range of government agencies that maintain anthrax, including the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration, have been asked to account for their specimens in detail, and to provide samples to compare with those used in the bioterror attacks.

In addition, organizations like the New Jersey Veterinary Medical Association and the New Jersey Pharmacists Association, which has set up a hotline to the F.B.I. to report large orders for anthrax vaccines, said that at least one of their members had been contacted by the F.B.I.

And at the American Type Culture Collection, a vast bioresource center that sells germs, based in Virginia, Nancy Wysocki, a vice president, said the center had ''a very close working relationship with many of the federal agencies, including the F.B.I.''

F.B.I. agents have also spoken to some pharmaceutical companies, including some based in New Jersey, company executives said. Some have been open with the bureau, others have asked, for legal reasons, for agents to present a subpoena before they would grant access to their files.

''We want to know what you have for anthrax, we want to see the documentation, we want to know who has access to it, where it's shipped from, who works with it, we want to know the protocols,'' said a senior F.B.I. official. ''We're not going to leave these facilities until every question is answered.''

Many university laboratories in New Jersey, Pennsylvania and New York have not been contacted in the investigation.

''I haven't seen neither hide nor hair of them,'' said Dr. John E. Lennox, a professor at Penn State University's microbiology department, though anyone interested in producing anthrax could find what they need in his laboratory. ''There isn't anything they would require that isn't in my lab,'' he said.

But Dr. Sulie Chang, chairwoman of the biology department at Seton Hall University in New Jersey, said F.B.I. agents called her several weeks ago, saying that they were contacting biology departments throughout the state.

Dr. Chang said they wanted to know if any

students had shown a sudden interest in anthrax. In fact, she said, a

student there had given a 15-minute presentation on the topic recently

and she gave the agents his name. She said she did not know whether they

followed up.

Dispute Over Daschle Letter

The F.B.I. was confronted with differing assessments of the anthrax found in the letter to Senator Daschle, a dispute among experts that illustrates the government's slowly evolving understanding of how to investigate an anthrax attack.

An initial analysis by the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, which specializes in biodefense, found that the material was very pure, very concentrated and highly dangerous. The Fort Detrick laboratory began studying the Daschle letter on Oct. 15 and delivered its first assessment to the bureau that night, a spokesman said.

Two days later, the F.B.I. sent a sample for additional testing to Battelle, a military contractor in Ohio that does secret work for the Pentagon and other government agencies.

Officials said the Army laboratory had irradiated part of the anthrax spores before studying them, a safety technique that leaves their aerodynamic and other characteristics undisturbed.

Apparently unaware that the Army laboratory had irradiated the material, Battelle used a different method, officials said, placing the anthrax in an autoclave and killing the spores with intense pressure and steam. Two officials said that this produced a far lower estimate of the concentration level and prompted Battelle scientists to conclude that the material was more likely to clump together, and thus less likely to waft through the air, than the Army scientists had estimated.

Both laboratories delivered reports to the F.B.I. on Oct. 22. One administration official said Fort Detrick found that the Daschle anthrax contained as much as one trillion spores per gram, much more than had been detected by Battelle.

Scientists quickly recognized that the tests had been conducted differently and agreed that Battelle should do a second study using irradiated material. A shipment was sent to Battelle on Oct. 25, one official said, which subsequently produced estimates similar to those of the Army scientists.

While the different findings created intense controversy in scientific circles, senior law enforcement officials said they had had virtually no effect on their conclusion that the material was very dangerous or on what they had told senior officials.

But officials said senior officials at the Department of Health and Human Services were sufficiently curious about the disagreement that they had asked the Army scientists to discuss their findings in person on Oct. 23. Officials said this week that the incident reflected how unaccustomed the bureau was to managing a complicated investigation that turned on scientific analysis.

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of criminal justice, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a 'fair use' of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

- Inform your media and political representatives of this vital information on 9/11. To contact those close to you, click here. Urge them to call for the release of classified documents and videos and to press for a new, impartial investigation.

- Explore the wealth of reliable, verifiable information on 9/11, including several excellent documentaries, in our 9/11 Information Center available here.

- Learn more about 9/11 and the secret societies likely involved in this powerful lesson from the free Insight Course.

- Explore inspiring ideas on building a brighter future by reading this short essay.

- Spread this news to your friends and colleagues, and recommend this article on key social networking websites so that we can fill the role at which the major media is sadly failing. Together, we can make a difference.

See our exceptional archive of revealing news articles.

Please support this important work: Donate here.

www.momentoflove.org - Every person in the world has a heart

www.personalgrowthcourses.net - Dynamic online courses powerfully expand your horizons

www.WantToKnow.info - Reliable, verifiable information on major cover-ups

www.weboflove.org - Strengthening the Web of Love that interconnects us all

Subscribe here to the WantToKnow.info email list (two messages a week)