Oakland Tribune

Interpreter quits over secrecy flap

Local man leaves post after refusing to sign agreement

barring him from discussing his job

By Josh Richman, STAFF WRITER

Article Last Updated: Monday, December 13, 2004 - 9:15:19 AM

BERKELEY -- For 18 years, Fred Burks put words in the mouths of America's diplomats and politicos, including two presidents.

But that ended last month when Burks resigned his part-time interpreting job with the State Department. He had to quit after refusing to sign a new secrecy agreement that would have barred him from ever mentioning anything about his work to anyone for the rest of his life.

"I'm not saying there shouldn't be secrecy -- it's obvious we need secrecy in certain areas," he said, adding he'd have no problem agreeing to keep secret "anything that could conceivably compromise national security. That, I would've been willing to sign."

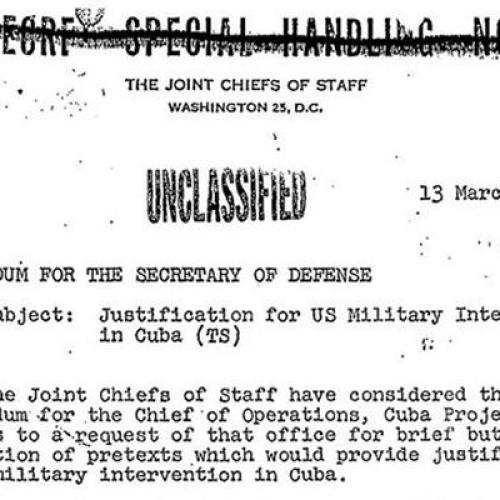

The contract the State Department demanded, however, could have kept him from ever telling anyone where he was going, whom he was with, any jokes or quips he overheard, even anything illegal he might witness.

"The contractor ... shall not communicate to any person or organization any information known to them by reason of their performance of services under this agreement that has not been made public, except in the necessary performance of their duties or upon written authorization of the contracting officer," the contract says. "These obligations do not cease upon the expiration or termination of this agreement."

That's too broad, Burks said. "To me it's a perfect symptom of the direction things are going with secrecy."

State Department spokesman Kurtis Cooper said the language is "basically boilerplate" and hasn't caused much of a row among most workers.

Secrecy agreements seem to be proliferating in the nation's capital. Labor unions recently complained that the Department of Homeland Security has demanded that its employees and contractors sign nondisclosure agreements barring them from sharing "sensitive but unclassified information" -- a gag order requiring workers to submit to potentially intrusive searches.

Some might be surprised Burks never before had been sworn to secrecy, but professional interpreters generally keep what they hear to themselves. For example, Article 2, Section A of the Code of Ethics of the Switzerland-based International Association of Conference Interpreters -- of which Burks isn't a member -- says members "shall be bound by the strictest secrecy, which must be observed towards all persons and with regard to all information disclosed in the course of the practice of the profession at any gathering not open to the public."

Burks, 46, is a gangly and enthusiastic New Jersey native who moved to the Bay Area at age 13 and has lived here, when not abroad, since then. He began interpreting for the government in 1986, soon after returning from two years in China. He did some Mandarin Chinese work at first, but found it easier to keep up with diplomatic terms in Bahasa Indonesia, the national language of Indonesia, which he'd learned while living there in 1981.

Most of his early work was on low-level diplomatic and political missions, but there were only a few qualified Indonesian interpreters available, and he rose through the ranks quickly. By 1995 he was in a White House meeting between President Bill Clinton, Vice President Al Gore, Indonesian President Suharto and others. In 2001 -- one week after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks -- he was in the Oval Office with President George Bush, Vice President Dick Cheney, Indonesian President Megawati, cabinet members and others.

He carried no secret security clearance through these and dozens of other major jobs, "which to me is a major mistake," he said. He sometimes was advised to apply for secret clearance, but the series of extensive background checks was never required of him.

And although the more stringent secrecy demand first was given to him during the Clinton administration's last days in October 2000, he never signed it, and nothing further was said of it. Only this fall, as the demand was incorporated into a whole new contract, did it become a sticking point.

The secrecy language is being presented to all of the State Department's approximately 1,600 part-time interpreters, so Burks doesn't believe he's being singled out.

Nor does he believe the demand has anything to do with his burgeoning work as an "armchair investigative journalist." He founded www.WantToKnow.info ("Revealing Major Cover-ups & Working Together for a Better World") in October 2002, gathering information from official documents and major media on subjects from the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks to government mind-control research. He now has taken up this work full-time, quitting his part-time nursing work and living off his savings.

Only once has anything from his interpreting work become part of his amateur journalism. After President Bush's "let me finish" comment during one of the October debates led some people to speculate he was being fed information through a hidden earpiece, Burks sent his site's subscribers an account of the 2001 meeting between Bush and Megawati.

Burks reported he had been amazed at the president's uncharacteristically long and detailed discourse on Indonesian affairs and since had come to believe the president was being electronically coached. His comments were reposted and quoted on anti-Bush sites throughout the Internet.

Coincidentally, Burks is also battling the government over his 1999 vacation trip to Cuba; the Treasury Department's Office of Foreign Assets Control wants to penalize him for breaking U.S. travel restrictions to that country.

Contact Josh Richman at [email protected] .